Episodes

Sunday Jul 09, 2017

Episode 3: Interview with Koraly Dimitriadis

Sunday Jul 09, 2017

Sunday Jul 09, 2017

Australian poet, author and performer Koraly Dimitriadis is the author of the controversial Love and F**k Poems, a stunning book of poetry which has been translated into Greek with rights sold into Europe. As an opinion writer, she has contributed to publications such as The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, ABC, SBS, Daily Life, Rendezview and The Saturday Paper. Koraly has turned her poems into short films, called The Good Greek Girl Film Project, courtesy of an ArtStart Grant.

In November 2016, Koraly's theatre show Koraly: I Say The Wrong Things All The Time, will premiere at La Mama Theatre, 205 Faraday Street, Carlton, from November 30th through to December 11th.

Get to know Koraly's work at KoralyDimitriadis.com.

What You'll Learn:

1. What inspired Koraly to write Love and F**k Poems.

2. Listen to Koraly read aloud three of her poems.

3. What to expect at Koraly's upcoming show and where to book tickets.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Elizabeth: Welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris, the show that connects Authors, Poets and Songwriters with their global audience. So I can continue to bring you high-caliber guests, I want you to go to iTunes, click Subscribe, leave a review, and share this podcast with your friends.

Today I’m delighted to introduce poet, author and actor Koraly Dimitriadis. Koraly is the author of the controversial bestseller Love and F**k Poems, a stunning poetry book which has been translated into Greek with rights sold into Europe. She is an opinion writer and has contributed to publications such as Daily Life, The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, ABC, SBS, Rendezvous, and The Saturday Paper. She has made short films of her poems called The Good Greek Girl Film Project, made possible with an ArtStart grant.

This November, Koraly’s theatre show, Koraly: I Say the Wrong Things All the Time, will premiere at La Mama Theatre, 205 Faraday Street, Carlton, Melbourne, from November 30 through to December 11.

Koraly Dimitriadis, welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris.

Koraly: Thank you for having me, Elizabeth.

Elizabeth: An absolute pleasure. Koraly, I’m a huge fan, and I love the poetry in your fantastic book Love and F**k Poems. A few things really impressed me about you. Firstly, the courage you show in writing so transparently about your life. Secondly, how you’ve handled the men who inevitably get the wrong idea about you. And thirdly, though some critics describe you as brash, you have a beautiful tender aspect. Can you please tell my listeners what inspired you to write your through-provoking book, Love and F**k Poems?

Koraly: I think it was a long journey of repression for me that led to writing the book, so I spent most of my life just doing what was expected of me by my culture and my family, and got married quite young at 22, not really knowing who I was, not having explored my identity or my sexuality. And all my creativity, because I was steered into a professional career as an accountant and a computer programmer, and so I lived a kind of repressed existence, both creatively, sexually, in many different ways, and my feminity as well…

Elizabeth: And certainly being an accountant would do that to you, wouldn’t it.

Koraly: Yeah well, it’s actually working as a computer programmer. I have an accounting degree. But yeah, I think it was definitely the birth of my daughter at around 27 and I started to question my life path and what I wanted to teach her, and what kind of role model I wanted to be for her. Did I want to teach her to do what everyone wanted her to do, or to be a strong independent woman that makes her own decisions and chooses her own life?

And up until that point I hadn’t really made my own decisions. I felt like I was influenced and just did what people decided for me. And I was very suffocated. And a few years later when I kind of exploded out of my marriage and my culture and the creativity came along with that. And I was writing a lot – a lot - of poetry at the time. I was doing a course at RMIT, and particularly I was studying with Ania Walwicz, and I remember going along to the poetry class and saying to her, “I want to be a poet. Just teach me to be a poet.” And she’s like “I can’t teach you to be a poet. There are no rules in poetry.” And I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was like “Are you for real? There’s gotta be some rules.”

And her encouragement really liberated me and I started writing a lot of poetry. I mean it was all happening at the same time, like coming out of my marriage and my culture. And then I remember one day I went and saw Ben John Smith at Passionate Tongues. I don’t know if you know him. He writes a lot of sex poetry, and very honest, kind of Bukowski kind of poetry. And when I went there, I never thought “Oh! You can actually write sex poetry, write about sex.” I talked with him, and he was really another instigator in me – you can write sex poetry, you can write about sex. I had just left my marriage and was exploring my sexuality, and the poetry just came along with it. So from there I wrote Love and F**k Poems, the zine.

Elizabeth: Which is so great, and there are so many aspects to it, which we’ll get to in the interview.

When you are writing, who or what is your major support?

Koraly: My major support? Sorry, what do you mean?

Elizabeth: So when you get into that zone of writing, do you draw on anything in particular? Do you draw on support from people, do you draw on support from coffee and chocolate?

Koraly: Well, I used to have a lot of sugar when I was writing, but I stopped eating sugar 2 years ago for health reasons.

Elizabeth: So what happened?

Koraly: I had some issues with my stomach, so it was really good for my health, and I haven’t turned back. I still have a bit of sugar, but not as much as I used to. But anyway, I probably draw on – I feel like writing is quite an isolating process and I don’t feel very supported when I’m writing; I feel alone. That’s what I would say, but that’s where the best poetry comes out. You’re actually face to face with your true, raw, honest self, and there’s a lot of fear there, but there’s also a liberation, going “This is who I am; this is how I feel”, and I’m going to turn this into a poem.

Elizabeth: And you do this so well.

Koraly: Thank you.

Elizabeth: So do you have a favourite poem, or is this like asking a mother if she has a favourite child?

Koraly: Umm, wow, that’s a really good question. Do I have a favourite poem. I guess I have poems that I think are my strongest poems, but no, I would say that I love all my poems equally, even the ones that haven’t been edited properly and might never see the light of day. And there are a lot of those.

Elizabeth: As I said, Koraly, I love all of your poems. However, I do have three favourites, one of which is Long Awaited Coffee Date. There is such an intensity within this brilliant poem. Can you please read it for our enjoyment?

Koraly: Oh, okay sure. Well no one’s ever told me that Long Awaited Coffee Date is their favourite poem.

Elizabeth: Well I’m unique … will tell you that.

Koraly: Okay.

The Long Awaited Coffee Date

When she steps out into the sinister night

She knows he wants more of her

So she leads him to a slim alley

Down the bluestone where nobodies meet

Their lips softly touching

Hands slithering down skin

His tongue in her mouth now

Lips wide, senses ablaze

And she knows she’s not going home

Tonight.

It’s dark when they enter his place

Quick to close the door,

He nudges her flush to the wall

A swift movement of her skirt

He pulls down her underwear

Locates her with his cock

And already he’s inside

Sighing in relief and ecstasy

This f**k months overdue

Her palms hit the wall

He entwines his fingers with hers

Slowly moving inside her

His lips and tongue on her ear

She removes a hand to touch herself

But his hand is quick to follow

He tells her to let him do it

But she pushes his hand away

Because she’s climbing now

And he’ll only delay it, ruin it

“F**king hell!” he curses

“Why do you have to control anything

Since the moment we met

Why won’t you just let me f**k you

Why don’t you just let ME f**k YOU!”

Elizabeth: Wow. (Applause.) That’s so great.

Going back to your book, in your acknowledgements for Love and F**k Poems, you thank a mutual friend of ours, the exceptionally clever editor and writer Les Zigomanis. Les has his own novel due for publication in 2017 with Pantheon Press, called Just Another Week in Suburbia. In the acknowledgements, I was intrigued to read the following: “Thank you to my editor Les Zigmanis for being the tough editor I needed who had every right to kill me during the editing of this book." (Laughter) So dramatic, Koraly! Can I ask what happened, without privacy invasion?

Koraly: Look, Les and I have an interesting relationship. Back in I think 2010, Busybird (Publishing) was the people who published a short story of mine.

Elizabeth: And what was it called?

Koraly: Blood Red Numbers, and it was about a psychotic computer programmer.

(Laughter)

Elizabeth: Was it based on anybody in particular?

Koraly: Yes, I did draw inspiration from working in the corporate world as a computer programmer.

Elizabeth: I never guessed!

Koraly: Les and I formed a professional relationship at that point, and he had been following my trajectory on Facebook with Love and F**k Poems. By the way when I published the zine I didn’t expect anything to happen with Love and F**k Poems; I just wanted to have something to sell at my shows.

Elizabeth: Can I ask you explain what a zine is for people who …

Koraly: Ah okay, it’s kind of like … It gets its name from ‘magazine’, and it’s basically like a small kind-of magazine without you like, usually you can print off it at a photocopy place. It’s not a quality book. And I just started putting a couple of copies in Polyester Books and it just started selling really well. And so when I’d sold quite a few copies in bookshops, and I was saying to Les one day, I said “Oh, I’ve got to write my next book.” And he’s like “What are you talking about, you know? You’ve got to turn Love and F**k Poems into a book.” And I was like, “Oh okay. Do you want to edit it?” And he’s like “Yeah, okay.”

Elizabeth: He’s editing my next book too.

Koraly: Yeah. He’s a very – I guess ‘cause I’m quite raw and honest and he’s quite raw and honest in his editing, he doesn’t hold back …

Elizabeth: He calls himself ‘brutal’, actually.

Koraly: Yeah, yeah, so I think, because we are both raw and honest, it creates a kind of interesting dynamic. But that’s what you want. I mean, my director Olga Aristademi from Cyprus who’s directing my theatre show, she is also very raw and honest. And I think I really draw to people that challenge me and challenge what I’m doing, because I want to be a better artist.

So Les is a great supporter of my work and he is always very helpful, and I really like working with him as an editor.

Elizabeth: You know, he’s wonderful. But I want to get back to that question, because I think you avoided the answer.

Koraly: Which one?

(Laughter)

Elizabeth: You were saying that he had every right to kill you. Now being a nurse, I find that really difficult to cope with.

Koraly: (Laughter) I think I meant that in a tongue-in-cheek way because I go over things a lot and I want things to be perfect and I feel …

Elizabeth: Perfectionist.

Koraly: And so … and also because you know, I feel like he invests a lot of time in editing and I feel I owe him for that. And I have a lot of gratitude, so that’s how I show my gratitude, by saying that he should have killed me.

(Laughter)

Elizabeth: We love gratitude, that’s for sure.

Your brilliant show – Koraly: I Say The Wrong Things All The Time – will debut on November 30th. What can theatre-goers expect from the show?

Koraly: Well, this is the first time I’m putting on a full theatre show with sets and lights and sound and it’s a big team. There’s the people at La Mama and there’s my own team of lighting designer and set designer and all those people. I think there’s ten of us, even though there’s just me on stage. I’ve taken my poetry and turned it into a play, a narrative, a story. And as part of that it includes actual acting rather than just performing my poetry, and creating a story that people can go away and think about. I really want to connect with people, mostly women, but people in general that have problems, that struggle with being honest with who they are, and people around them.

Because society does want to put us into pigeon holes, and I’ve experienced that before. Like I said, you know, my own experiences of – you know – being steered in particular directions and not being who I want to be. I want to inspire people to be themselves and to not be afraid to be themselves, and to know that, yes, it is difficult sometimes, especially in certain cultures and religions, to stand up and be who you want to be. And there are prices and sacrifices to be made, but it’s so worth it, because it’s your life. You only have one life. And why wouldn’t you want to live that life how you want to live it. Why do we have to live according to how other people expect of us? We should just live our own lives and be happy. So that’s what I want to inspire people to do as part of this work.

Elizabeth: And I find you incredibly inspiring, so thank you so much … being so courageous.

Koraly: Thank you.

Elizabeth: Another one of my favourite poems is My Words.

Koraly: Another person actually said that to me recently. Like, really? Like, it’s not one of my favourites. (Laughs)

Elizabeth: Yes. And do you know why, Koraly? Because I feel it reveals your depth. Can you please share that with us?

Koraly: Ah, okay. Yes. I’m actually going to read that poem at a White Ribbon event tomorrow.

Elizabeth: Oh, wow.

Koraly: And also give a speech. And they want me to read that one too, and I’m like, “Oh, that’s interesting.”

Elizabeth: Do you want to talk a little bit about that event?

Koraly: Yeah, it’s just a event about violence – invisible violence against women, and how emotional manipulation can be a form of violence, and how do we empower women to stand up against that. And I’ll be sharing my story like I did with you, you know, what I experienced growing up.

Elizabeth: That’s wonderful, and again, very brave. So My Words …

Koraly: My Words

A long time ago when I was another person

And I wore another face

I wrote short poems to try and make sense of myself.

One, with every wrong footing there is a right

Two, two steps in the wrong path equals one in the right

Three, do not abuse yourself for the blessing of a mistake

Four, regret is a naïve word – pray for mistakes

But that’s all bullsh** when your actions hurt people you care about

Like I care about you.

I have cried many tears in my life

All about things people have done to me, and my hardships, and my sad, sad life

I’m 32 years old, and tonight, for the first time,

I’m crying tears for someone else.

Pain I inflicted with my words

Oh yes! My wonderful words, my powerful narcissistic words.

Oh yes! I’m a poet, and don’t I do it so well.

I can make the crowd collapse into silence,

Like your silence, your hurt silence.

I wanted to crawl into the phone, scoop up the pain in your chest,

And bury it inside me

Not just the pain I caused, but the other pain too,

The pain you hide from me.

I heard it clearly for the first time tonight.

In my mind there is an image of the person I dream to be

You make me want to be that person.

Pity I had to hurt you to realize that, or to realize I care

So much more than I thought I was capable of

And so I write this poem, a pathetic attempt to make it better

Even though the decision you made was actually best for me

And you proved you cared more than my self-sabotaging mind allowed me to believe

So here’s to my attempt to make it better

Here’s to my bullsh** words; it’s all self-indulgent crap

My actions hurt people I care about

They can hurt people I care about …

People I care about …

Like I care about you.

Elizabeth: Beautiful, beautiful. (Applause)

Koraly: Thank you.

Elizabeth: What do you do in your spare time to unwind, other than write poetry?

Koraly: (Laughter) Do single mothers actually have that time?

Elizabeth: I don’t know.

Koraly: I would say that I love to go out dancing.

Elizabeth: Oh wow, what sort of dancing? The Spanish Festival’s coming up this weekend.

Koraly: Umm, anything like – I mean I like dancing to alt rock. I also like dancing to techno music, just anything.

Elizabeth: You’re a dancing queen.

Koraly: I’ve been told I’m a good dancer by my director Olga as well, so …

Elizabeth: Pity we can’t see a demonstration on a podcast, Koraly.

Koraly: Actually I’ll be dancing in my theatre show.

Elizabeth: I’ll be there.

Koraly: So dancing I would say, and also …

Elizabeth: I might come up and join you on stage. (Laughter)

Koraly: Dancing and also spending time with family and friends and going and seeing bands, that kind of stuff.

Elizabeth: Any particular bands you love?

Koraly: I like going to the local pub and listening to whoever’s playing,

Elizabeth: Do you have a website or blog where my listeners can find out more about your work?

Koraly: Yes, I have a website: www-dot-Koraly-Dimitriadis-dot-com. I used to have a blog, but I’ve since closed it because, I used to blog quite a bit when I was kinda in that explosion phase. I was blogging a lot and I kept blogging up till a year ago when I started getting articles published in publications. And then I just wanted to focus my energy on writing articles, and so I closed my blog. But people can go to my website and there are links to all the articles that I’ve published, there.

Elizabeth: And there’s links to some film too, isn’t there.

Koraly: Yeah, there’s links to my films.

Elizabeth: That’s great, really great.

Koraly, this is a signature question I ask all my guests: What do you wish for for the world, and most importantly, for yourself?

Koraly: I wish for no war, and for peace, and equality across races and gender and sexuality of course. And a brighter future for my daughter, a world that is more peaceful than what it is now, so I don’t have to worry about her when I’m gone.

Elizabeth: Can I ask how old is she?

Koraly: She’s 9. And also for myself, I would like to progress with my art and make a living from it.

(Laughter)

Elizabeth: Yes, for sure.

Koraly: That’s what I would really like. So but also I would like to inspire women and empower women, and that’s ultimately why I do what I do and put myself on the line.

Elizabeth: I think you certainly do inspire women. Do you want to touch on some of the male reactions – I know you’ve had some fairly dramatic male reactions. And as much as we love men and admire them and so forth, sometimes I think they get the wrong idea, and need to be put on the straight and narrow with your work, so here’s your chance if you’d like to take it.

Koraly: I think actually in Australia, the men are quite well-behaved when it comes to my art. They will contact me and tell me they like my art but they won’t usually make a pass at me. Whereas in Greece and Cyprus the men won’t hold back and they will send me very explicit messages and they will make commentary on my body, and it becomes … And I think the reason for that is because women’s writing overseas is not very respected. In Greece and Cyprus, especially the fact that I write about sex, makes me even less respected and probably means that I just want to have sex and will you have sex with me, that kind of thing.

I don’t get that in Australia. A train driver once wrote me a note about how much he likes my work, on a train technical form, and sent that to me, and I kept it. I thought it was quite funny. But you know he wasn’t making a pass at me. He was commenting on my work. And that’s fine – I don’t mind that. What I mind is when men comment on my body and think that I just want to have sex. I just ignore them, like, as if, you know.

I mean, most of the poems in Love and F**k Poems are about one guy as well, so it’s not … you know … it’s not like … People get this idea that I’m like sexually wild or whatever, but it’s kind of the opposite, so …

Elizabeth: I think it reflects more so on themselves, maybe their hopes and wishes for their world.

I want to wrap up with one of your poems which resonates so well with me and my female friends and my enlightened male friends, and the poem is Temple.

Koraly: Ah, Temple. Okay.

Temple

My body is a temple you shall not cross

Unless you are worthy of my communion

I have been angry, desecrated my spirit,

But I needed to do that to arrive here.

Because

I deserve happiness

I deserve love

I deserve someone who will give to me

Just as much as I give to them

And I want it – I want love

L-O-V-E

Love.

I want to embody ecstasy inside alleys

In dark corners, underneath stars,

Everywhere with my man

Explore our darkness and our light

And if you’re not looking for the same thing

MOVE ON.

And in the meantime, men can come, men can go,

I’m not looking

I’m happy on my own

And I will worship my own

Temple.

Elizabeth: So powerful and beautiful. Thank you. I have tears in my eyes.

Koraly: Thank you.

Elizabeth: We look forward to your fabulous theatre show, Koraly: I Say The Wrong Things All The Time, at La Mama Theatre, on November 30 to December 11. How do we book tickets?

Koraly: Through La Mama website. So if you Google “Koraly: I Say The Wrong Things All The Time”, it should come up.

Elizabeth: And look, I’d like to contest whether you do or not, because you say plenty of right things, Koraly

(Laughter)

Koraly Dimitriadis, thank you so much for guesting on Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris. And remember parents, when reserving your tickets for Koraly’s show, it is not a child-friendly show, so book your favourite person to mind your children, and come along and enjoy the genius of Koraly Dimitriadis.

Thank you everyone for tuning in to Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris, and may all your wishes come true.

Koraly: Thank you for having me.

[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

Sunday Feb 12, 2017

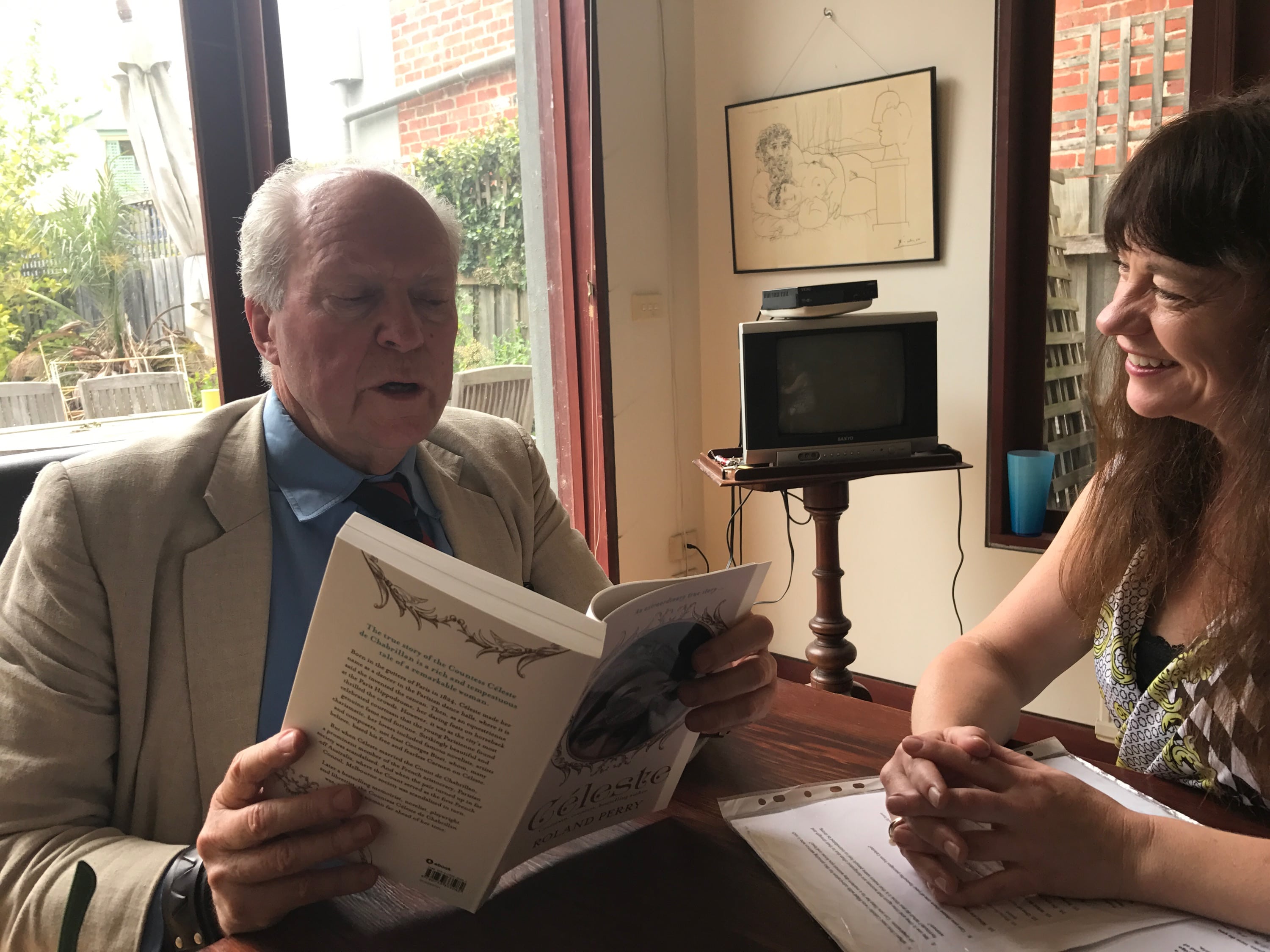

Episode 7: Interview with Michael Salmon

Sunday Feb 12, 2017

Sunday Feb 12, 2017

Elizabeth Harris visits Michael Salmon's studio in Kooyong, Melbourne, and learns from the children's author, illustrator, and entertainer of school children, what 50 years in the arts has taught him about -

- Learning to trust your instincts about what early readers find funny.

- The importance of branching out and diversifying if you want to thrive as an author and illustrator in the long term.

- How your personality and people skills (or lack thereof) can influence your success in the arts.

- The pleasure of giving back to the community when you've attained a measure of professional success.

How did a beloved children's book make it to the centre page of a newspaper, and its main character become 600 kilos of bronze outside a public library in the nation's capital?

What's the connection between Michael, Healthy Harold (the Life Education giraffe that visits schools), and the Alannah and Madeline Foundation?

Follow Michael as he travels around Australia visiting Indigenous schools and schools with students of diverse ethnicities, backgrounds, and levels of English fluency.

Find out more about Michael Salmon's work at MichaelSalmon.com.au.

Notes:

Robyn Payne is an award-winning multi-instrumentalist, composer, producer and audio engineer of 25 years’ experience in the album, film, TV and advertising industries.

She composed the music for the theme song 'Victoria Dances', which is featured in host Elizabeth Harris' children's book, Chantelle's Wish, available for sale on Elizabeth's website at ElizabethHarris.net.au.

The lyrics for 'Victoria Dances' were written by Elizabeth Harris.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Elizabeth: Welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-Tête with Elizabeth Harris, the global show that connects authors, songwriters and poets with their global audience. So I can continue to bring you high-calibre guests, I invite you to go to iTunes, click Subscribe, leave a review, and share this podcast with your friends.

Today I’m delighted to introduce the highly creative and entertaining children’s author and illustrator, Michael Salmon. Michael Salmon has been involved in graphics, children’s literature, TV and theatre since 1967. He started his career with surfing cartoons, and exhibitions of his psychedelic art, and then joined the famous marionette troupe – The Tintookies – as a trainee set designer stage manager in 1968 (the Elizabethan Theatre Trust, Sydney).

Since then his work has been solely for young people, both here in Australia and overseas. His many credits include his Alexander Bunyip Show (ABC TV 1978-1988), pantomimes, fabric and merchandise design, toy and board game invention, writing and illustrating of 176 picture story books – which Michael I’m absolutely flabbergasted and astonished and in wonderment at, and everybody’s laughing at that, or maybe he’s laughing at me, I don’t know. (Laughter)

I’ll say it again – 176 picture story books for young readers. Several million copies of his titles have been sold worldwide. Michael has been visiting Australian primary schools for over 40 years. His hour-long sessions are interesting, fun, humorous and entertaining, with the focus on students developing their own creativity, which is just fantastic. Suitable for all years, many of these school visits can be seen on Michael’s website, which I will ask you to repeat later.

Michael: Okay.

Elizabeth: Several trips have been up to the Gulf of Carpentaria Savannah Schools and to the remote Aboriginal community Schools on Cape York Peninsula, as a guest of EDU.

EDU – what is that?

Michael: Education Department, Queensland.

Elizabeth: The Australian Government honoured his work in 2004 by printing a 32nd Centenary, special edition of his first book The Monster that ate Canberra – I like that - as a Commonwealth publication … for both residents and visitors to our Capital. Every Federal Politician received a copy.

Michael: Even if they didn’t want it, they got one.

(Laughter)

Elizabeth: Michael was also the designer of ‘Buddy Bear’ for the Alannah and Madeline Foundation (Port Arthur 1996). The Foundation financially supports Children/Families who are victims of violence/violent crime; they are currently running an anti-bullying campaign in Australian Schools.

In 2010 the ACT Government further recognized his work by commissioning a bronze statue of his first book character ‘Alexander Bunyip’. Unveiled in April 2011, it stands next to the new – and I’ll get you to say this, Michael …

Michael: GUN-GAH-LIN.

Elizabeth: Gungahlin Library in our Federal Capital. Thank you for saying that.

Michael has presented ‘Bunyip-themed history sessions’ for audiences of School Children at the National Library of Australia since 2011. School touring and book titles continue, which I’m blown away by, because you’ve written and illustrated 176 books!

Michael: Some of those were activity books, to be fair, but they were necessitated – writing, the requirements of children, and illustrations, so they were all lumped in together, basically.

Elizabeth: So Michael Salmon, welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-Tête with Elizabeth Harris.

Michael: Thank you very much. It’s a pleasure, and thank you for visiting my studio here in downtown Kooyong, Melbourne.

Elizabeth: We are delighted to be here – Serena Low and I, everybody – Serena being my wonderful tech support.

Michael, we have been Facebook friends for some time now, which is a wonderful way to keep in contact with people. But do you think social media has affected children adversely, and stopped them from reading and enjoying children’s literature?

Michael: Do you know, in order to answer some of the questions you asked, I probably pondered this one the most. It’s strange times. I’m 67 years old now. If I go back to when I was a teenager …

Elizabeth: Looking very dapper, I may say.

Michael: Yes, thank you, thank you. (Laughter) It’s amazing what no exercise will do. (Laughter) Things have changed so much. If you go back to the fifties and sixties – which both you ladies will have to look at the old films and see reruns of Gidget and all that kind of stuff – however, the main communication of young people several, several decades ago, socially, would have been the telephone.

Invariably, houses only had one line that mums and dads would need. But the girls mostly – and perhaps the boys too – would be on the line talking to their friends and all this kind of stuff. And that was the only direction of communication. Perhaps letters and whatever, but certainly the telephone was the main thing. Now how things have changed these days.

Having 12 grandchildren ranging from – what are they now, 2 to 24 – I’ve seen a whole gamut, and I see daily just how much social media – the iPads, tablets and things – are taking up their time and the manners in which they take up their time.

Elizabeth: What a wonderful family to have!

Michael: Well, it’s certainly a bit like a zoo (laughter) – I hope they don’t mind me saying that – and I’m the head monkey, but that’s about it. That’s true.

But if you think of a child – and one of the main loves in life is visiting schools, and over the many years in Australia I’ve visited many, many schools – and just see what the teachers are up against these days. And often the teachers are – it’s well-known – surrogate parents on many occasions. Often it’s left to teachers, whether it be librarians or very kind teachers …

Elizabeth: Challenging job.

Michael: … To instill in the children a love of literature and how important reading is.

But I think of going back to my youth and my toy soldier collection and making and making balsa wood castles and Ormond keeps and whatever it may be, playing in my room with this fantasy world I had grown up in.

Elizabeth: What an imagination!

Michael: Well, my father read to me – when it first came out, back in the fifties, and I was quite young, but – The Hobbit, C.S. Lewis and the Narnian … – beautiful. I was brought up in those kind of – and he also read most of Dickens to me, as well as Kipling. Quite incredible stuff. So my father was a major player in my love of literature.

And I’m not sure that it happens hugely these days, but I grew up in a world of imagination. And it wasn’t any great surprise to my parents that I entered the world I’m in, which is the fantasy world of children, because I never got out of it, basically. 67 years we’re looking at at the moment. I would say mental age is about 8 or 9. (Laughter)

Elizabeth: But you make very good coffee for a 9-year-old, Michael.

Michael: But it did eventuate that sitting in my studio in the early hours of the morning, if I start laughing at a concept or whatever, I know full well through the passage of time that preppies or Grade Ones or Twos or kinders will start laughing at it too. So you get to trust your judgement after a while in the arts. You get to know where your strengths are.

But going back to your original question, I have a couple of grandchildren who are absolute whizzes on their tablets. They’ve gone through the Minecraft thing; they’ve gone this, they’ve gone that. Almost an obsessive kind of stuff there.

Elizabeth: It’s an addiction, I think.

Michael: Sometimes, you must take time away from the use of imagination. Because let’s face it, in using our imagination, our creativity – and creativity can be cooking a magnificent meal, it can be keeping a well-balanced house. There’s all kinds of creativity, or it could be the artist creativity, but that’s such an important thing, of finding who we are.

Elizabeth: Yes.

Michael: And to have children taken away to a certain extent Magic Land which is absolutely fine until they become obsessive or addictive, as some of these things are, there’s a great danger that children are – shall we say – not able to evaluate or to progress their natural talents etcetera coming through, especially in the arts.

Elizabeth: I totally agree with you. Michael, you’ve written and illustrated so many books. As I’ve mentioned a couple of times, 176. How do you decide what to write about?

Michael: Well, it’s probably – I’ve always written from a cover idea. There’s a book of mine going way back. It’s one of my old favourites, a very simple one, which is called The Pirate Who Wouldn’t Wash. And when I talk to children and they say where do you get your ideas from, I say sometimes you get two ideas that are unrelated and you put them together, and because hopefully my books are rather funny and I was brought up in the fifties on things like The Fabulous Goon Show, Peter Sellers, and Spike Milligan. I loved Monty Python which was a direct sort of baby from The Goon Show. So my love of comedy has always been UK-based. And so that strange juxtaposition of whatever, so I thought, okay, a pirate, and perhaps a person who doesn’t like to wash. And you put them together and you have the pirate who wouldn’t wash. And then you simply – it’s easy if you have a vivid imagination – you list a whole lot of encounters or what could happen to a pirate who wouldn’t wash.

Elizabeth: Could we talk about that? I’d love to talk about that.

Michael: A monster, and then someone who doesn’t like vegetables. Which was one of my stepsons, William, and he was ‘Grunt the Monster’, which was one of my early characters. Refused to eat his vegetables. His teachers went to great lengths to find out how he could eat them, disguise them in milkshakes or whatever it may be. So it was William I was writing about, one of my younger stepsons at that stage. And at university when he went through Architectural course, he was called Grunt, because they knew full well the book was based on him. So it’s good sometimes to disguise – but nonetheless feature things you see around you.

Elizabeth: How did he cope with it?

Michael: He loved it, he loved it, he loved it.

Elizabeth: He got attention?

Michael: He got attention, all that kind of stuff, and he had one of his best mates who let everyone know that he was called ‘Grunt’ – that was sort of his name. But at some stage, I think he uses that – he lectures in Architecture around the country these days. He’s gone and done very well, dear William, and he will sometimes use that as a joke.

Elizabeth: Yes. Icebreaker.

Michael: Icebreaker, exactly.

Elizabeth: Was there a pivotal person who influenced your career? And if so, can you tell us how they inspired you?

Michael: Probably apart from the people I’ve mentioned previously, the Tolkiens and the Hobbits and the Lord of the Rings and the C.S. Lewises and that sort of thing, I’ve always loved the classic British thing like Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons. These are very famous books that everyone read at one stage.

Back in those early fifties, my father was at Cambridge University so we were hoisted out of New Zealand; we went to live in the UK, and it was such a great time for a child to be in the UK. It’s still suffering war damage from Second World War, and London still roped off sections of it - the Doodlebugs, the flying bombs that the Germans sent over to hit London. So it was a rather strange place, but the television was brilliant. I was a Enid Blyton fan, a foundation member of the Secret Seven Club.

Elizabeth: Were you really.

Michael: Even though based in Cambridge, we looked forward to every month of the Enid Blyton magazines, so I grew up on The Faraway Tree and the Secret Seven and the Famous Five. I had my badges, I had all the merchandise. But also on the television in those days was a show we never got to hear in Australia – Muffin the Mule. There was also Sooty the Sweep, Bill and Ben the Flowerpot Men. Andy Pandy was another one. Most of those were for kindies and little bubs. Basil Brush was a little bit later on. And British television was always superb, especially for children. Blue Peter and some of those famous shows was a little bit later on. I mention this because I had ten years of my own show on ABC which you’ll learn later on, and used puppets and things which I’d seen being used on British television.

Elizabeth: Can you tell us about that show please?

Michael: The show itself … When Alexander first became a character, it was a Michael 'Smartypants book', a little book I had published in 1972. This is The Monster That Ate Canberra. And this basically the genesis of the television show. I thought I would do a – I wasn’t a university student but it was like a smartypants university student publication, because the bunyip himself was not the Kangaroo – was in fact an oversized pink bunyip, more like a Chinese dragon. However, the monster was the public service, and so it was like a joke about the public service. Because back in those seventies and late sixties, large departments were being taken from Melbourne and Sydney and relocated in Canberra, Melbourne Commonwealth finance and other things, so Canberra was being flooded with the public service. And that was why Canberra was being set up, but anyway, as a youngster back in 1972 when I first wrote that book, I envisaged this large King Kong kind of character over Civic, which was the main principal shopping centre, the oldest shopping centre, going on Northbourne Avenue as you come in from Sydney.

There’s this large monster devouring things, but this monster has a problem: he is short-sighted. Anyway, he saw the buildings – the famous, iconic buildings of Canberra as objects of food. So put them into – like the Academy of Science, a gigantic apple pie; the National Library, which was recently built, at that stage and still looks like a gigantic birthday cake; and I had the Carillon looking like a Paddle Pop or something like that, which are all to do with objects of food. And the bunyip devoured them. And the Prime Minister – the original Prime Minister back then was (William) “Billy” McMahon, and when he chucked, we had then changed to Gough Whitlam. So Prime Minsters changed within the reprints of this book. The best thing about this … way way back when Gough Whitlam became our Prime Minister, one of the first things he did was institute an office that had never been there before, called the Department of Women. It was there specially to consider and to aid passage of women in Australia into jobs and a whole range of things that had never been heard before in a male-dominated kind of world.

Elizabeth: I’ve always been a fan of Gough, so I must say … (Laughter)

Michael: Well, Gough appointed a single mum called Elizabeth Reid – Liz Reid – and she was a very famous lady and she really championed the cause of women, you know, equal rights, and these ridiculous things that should have been fixed a long time but hadn’t. So Liz Reid was pictured in the centre page of the Woman’s Weekly, soon after Gough – this was one of his first appointments, Liz Reid. And there was Liz with her little bub – so she was a brand new single mum.

Elizabeth: Oh wow. Which in those days would have been scandalous, wouldn’t it.

Michael: Oh yes, but Gough was famous for that. He already went out specially with the arts. Regardless of how he was considered as a Prime Minister, he was certainly a great patron of the arts, Gough Whitlam.

Elizabeth: As I said, I’m a fan.

Michael: In this picture, centre pages of Woman’s Weekly, double spread, was little bubba. And in little bubba’s hands, supported by his mother, was a copy of The Monster That Ate Canberra.

Elizabeth: Wow! How did you feel?

Michael: I thought, “Fantastic!” I got a call within a week from one of the biggest educational publishers in the world, called McGraw-Hill, asking “Can you tell us a little bit about this? And I was described as this is probably not how I would think, and I said “No, but thank you very much for calling.” So the most unusual thing sort of kicked up, and we were reprinting this book again and again for Canberra, because Canberra was laughing its head off.

Elizabeth: Good on you Ms Reid – and baby.

Michael: So we had a theatrical presentation, pantomimes based on it with the local Canberra youth theatre. ABC then serialized it on radio, and then came to me – this was about 1977 or so – saying, “Would you consider having Alexander Bunyip on television?”

Elizabeth: Wow.

Michael: And I said “Yes please, thank you very much.” And it was through a mate of mine, quite a well-known scriptwriter for Australian films called John Stevens, and also director of plays and whatever around Australia, and he was one of the directors of the young people’s programs in ABC, who were based at that stage in Sydney.

Anyway, Alexander got on television through this rather, uh, strange path he led, entertaining the people of Canberra.

Elizabeth: Can I ask you with that, and throughout your life, you have enjoyed such great success, and certainly rightly so. Have you found that there’s been what has been seen as insignificant moments, turn into huge, huge achievements for you?

Michael: Well, (I) try to step away from cliché but sometimes it’s hard to, when I say you make your own luck. But the fact that that for example, one of my main – I love it – the statue of Alexander Bunyip, 600 kilograms of bronze outside the library.

Elizabeth: In that place I can’t pronounce.

Michael: Gungahlin, that’s right, Gungahlin.

Elizabeth: I’ll practise it.

Michael: I’ll tell you how that happened. Sometimes on Google if you’re an artistic person and you’re an author or illustrator, if you just put your name in and see what’s the latest thing, are there any new entries. Sometimes schools put in things in comments or whatever. Sometimes odd things about your life come up – business life, work life. And there was a situation that occurred, when Gungahlin Community Council had discussed whether – because John Stanhope, who was the chief minister of the ACT at that stage was putting up statues left right and centre, because he wanted a lot of edifices in Canberra to entertain people.

Elizabeth: He was a visual.

Michael: Yeah, visual person. And someone said, “Why don’t we have Alexander Bunyip?” and there was general laughter. But that was supported in the Council vote of Hansard, you know, the documented notes taken in that particular Council session, and I saw this online. And so I merely wrote to this person, sent them one of the more recent copies of The Monster That Ate Canberra, and said “That sounds great. Let me know if I can help.”

Elizabeth: Absolutely!

Michael: Gosh, one thing after another happened, and the head of the Council Alan Kirlin, with John Stanhope, got it organized, and within a year there was a brand new statue being launched by John Stanhope, one of the last things he did before he resigned. He’d done some magnificent work in Canberra. So new ministers were appointed etcetera, so John – the statue was launched, and I made a speech which was dedicated to my mum, who had died the year before. She was a Canberra girl, and I thought that would be nice to dedicate, at least mention her. I’m sure if she were around - in ethereal style - she wouldn’t miss out on that one, I can assure you.

Elizabeth: I’m sure.

Michael: But when the statue was dedicated – the statue stands there –

Elizabeth: Can we go back, because I would like to talk about that speech about your mum. Can we talk about that?

Michael: Yes. Well, my mother Judy, as I said who passed on in 2010 – the statue was put up in 2011 – was a very … went bush Port Douglas many years ago, before Christopher Skase was up there.

(Laughter)

So I used to go up there and visit her. A hurricane holiday house, which is simply a house in Port Douglas without any windows. It was up in the hills towards the Mosman River valley.

Elizabeth: For those who don’t know Christoper Skase, can you please touch on him briefly.

Michael: Christopher Skase was one of our major financial entrepreneurs who died over in a Spanish location owing millions of dollars to many people. He was like a younger brother of Alan Bond. That’s where Christopher Skase fitted in. I don’t think New York or Spain ever really sort of –

Elizabeth: Recovered.

Michael: Recovered from the Australian paparazzi to see whether Skase was in fact dying or whether he was in a wheelchair with breathing apparatus, wheeled out by his ever-loving wife Pixie, who is back safely in the country now. But that’s by the by.

(Laughter)

Michael: My mother was a fairly gregarious character.

Elizabeth: Bit like yourself.

Michael: (Laughter) Pushy.

Elizabeth: No, no, no. Delightful, and entertaining.

Michael: Judy was one of the younger daughters of her father, my grandfather, Canon W. Edwards – Bill Edwards. He was a young Anglican curate who’d been badly gassed on the fields of Flanders and the Somme in the First World War.

Elizabeth: Oh dear.

Michael: But he was an educationalist, as well as a very strong Anglican within the church. So he was sent on his return out to Grammar School looking after that in Cooma. When Canberra was designated as the place to have our new capital, the Anglican Church from Sydney said, “Please harness up one of the buggies, and take six of your seniors and go look at four different venues in Canberra that we are looking at to have a brand new school.”

Elizabeth: Wow.

Michael: And they chose the most beautiful place, in a road called Mugga Way just at the bottom of Red Hill, which is Canberra Boys’ Grammar. He was their founding Headmaster.

Elizabeth: Was he!

Michael: But the fact was that they settled on that because they pitched their tents under the gum trees. They woke up with the sound of intense kookaburra noise, and thought this was perfect for a grammar school, or any other school for that matter.

Elizabeth: Oh, beautiful.

Michael: They were all talking and whatever it was.

Elizabeth: Bit like sounding the bell, you know.

Michael: (Laughter) So going back to those days, that was the start of Canberra and my family going back there to the thirties of last century. However, back in those days in the Second World War, my father had graduated from school in New Zealand, and was sent across as one of those New Zealand young soldiers to become an officer at Duntroon, the training college. The Defence Academy they call it now, but good old Duntroon. So when he graduated, it was the end of World War Two, and he was sent up to war crimes trials in Japan, as one of his first things the Aus-New Zealand ANZAC forces when they went up there to look after things for a while.

But my mother was quite a brilliant lady, and she would always be the one painting and decorating and doing all this kind of stuff. Always a dynamic kind of person. And apart from loving her very much as a mum, she instilled in me this gregarious, rather exhibitionist kind of thing.

Elizabeth: (Laughter) Thank you Judy. It’s Judy, isn’t it. Thank you Judy. I know you’re here.

Michael: So Judy was responsible for – in younger, thinner days, long hair, beads, not necessarily hippie stuff but just total exhibitionist kind of stuff.

Elizabeth: Oh I’ve seen photographs of this man, everybody. My goodness, what a heartthrob.

Michael: I looked like I could have been another guitarist in Led Zeppelin or something.

Elizabeth: I’m actually just fanning myself with my paper. (Laughter)

Michael: But anyway, it’s all a bit of fun.

Elizabeth: Did you ever sing?

Michael: No, no, no. I was actually a drummer at one of the schools I attended.

Elizabeth: Were you? I like drummers.

Michael: Yes, but not this kind of drummer. In the pipe bands at Scotch College, Sydney. I was a tenor drummer.

Elizabeth: Okay.

Michael: So they have the big, the double bass drum or whatever and the tenor drums and the drumsticks - I forget the name – like the Poi they have in New Zealand. And the tenor drums – you have to have coordination if you want to play the tenor drums as you march along in your dress: the Black Watch dress.

Elizabeth: Isn’t learning music so important, which reflects in other areas?

Michael: It is, it is.

Elizabeth: Can we talk about that?

Michael: Well, I think that – not being musical but having written lyrics in my pantomimes – and down at a very amateur level worked out what a bunyip would sing about, or go back to an early blues song or doo-wop kind of song when Alexander is stuck in a zoo in the pantomime. So I had great fun.

So my musical experience – I was lucky to have some very clever people, including one gentleman who until a few years ago was one of the Heads of Tutors at Canberra School of Music called Jim Cotter. Now Jim Cotter and I – he wrote my first music for me, for the pantomimes I used to do way back in the early days. And then Peter Scriven – he was the head of the Tintookies Marionette Theatre, who were all under the auspices of the Elizabethan Theatre Trust in Sydney at Potts Point. And Peter had engaged him to do – I was doing some sets – it was the first show, our first children’s show at the Opera House – and I did the costumes for Tintookies. It was a revamp of what Peter Scriven had been doing back in the fifties. And Jim had some brand new music, and so my musical experience was purely admiring music and talented people who did that, realizing that it was not my forte.

Elizabeth: Aren’t they clever.

Michael: Nonetheless, by writing lyrics and giving some vague, vague “rock ‘n roll and I like it” -like, you know. Not exactly “Stairway to Heaven”, you know what I’m saying?

Elizabeth: (Laughter) Who was your favourite band at that stage?

Michael: Ahh, I grew up in the Sixties. I got myself a hearing aid the other day. You can hardly see it – one of these new things. But essentially, I’ve had to, because I spent a lot of my younger life surfing in the eastern beaches of Sydney. The promotion of bone growth over the ear – there’s some kind of term for it – and they had to cut away the bone if I were to hear properly. And I thought, I don’t want my ear cut, so I’ll just leave it as it is at 67. But also too, I do attribute some of those early groups to my lack of hearing these days, because I did study for my exams with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones. Pretty much one of my favourite groups of all time was a group that spread, with different members going to different other groups, were The Byrds in America. Dylan songs. “Mr Tambourine”.

Elizabeth: Yes. Was it Eric – Eric somebody? Or did I get the wrong group.

Michael: We’re talking about David Crosby, Gene Clark, Jim McGuinn who changed his name and became Roger, or was it the other way round. But they had the Dylan. They came out with “Mr. Tambourine Man”.

Elizabeth: Yes, I know that song.

Michael: Their next one was ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’. Then they went into more Dylan of, “All I Really Want to Do”. And these are hits of the Sixties.

Elizabeth: You could sing a few bars.

Michael: No I couldn’t. Not even Dylan-style.

(Laughter)

But I love those songs, mainly because -

Elizabeth: They’re great.

Michael: Jim McGuinn had a 12-string guitar, and it was this jingly-jangly feel to their songs that I loved dearly. But another group which I must tell you, because I met up with them in real life, which is one of my favourite groups, is The Seekers.

Elizabeth: Oh! Miss Judith!

Michael: Now Keith Potger is a good mate of mine. We go for gentlemen’s clubs like Savage Club; he’s a member of Savage, enjoy long lunches, and often with some other guests.

Elizabeth: Athol Guy?

Michael: Yes. And Judith Durham – where you’re sitting there – came and sat down there with her manager a few years ago.

Elizabeth: My goodness!

Michael: She’d seen a presentation –

Elizabeth: She’s beautiful.

Michael: Oh, magnificent. And her voice!

Elizabeth: Angel.

Michael: Judith had seen a production by Garry Ginivan, who is one of the principal Australian children’s entrepreneurs for theatrics, theatres. He’s just finished doing Hazel E.’s Hippopotamus on the Roof kind of stuff, and I’m not sure if he’s doing Leigh Hobbs’ Horrible Harriet. Now that’s going to the Opera House. I’m not sure if Garry Ginivan’s doing that for Leigh. He did for Graeme Base. He did My Grandma Lived in Gooligulch, and also brought packaged stuff like Noddy and Toyland, Enid Blyton and other stuff like The Faraway Tree.

So anyway he was presenting Puff the Magic Dragon – and I’m just looking around the room to find a graphic of the poster, because I’d designed Puff the Magic Dragon.

Elizabeth: Did you?

Michael: And they used that for all the promotional material and stuff there, but it was the puppet that I designed. And Judith went along to see – it was at The Athenaum Theatre here in Melbourne, a few years ago now.

Elizabeth: Lovely theatre.

Michael: And she liked the whole idea of the dragon, and she rang me. And so here was this most beautiful angel on the other line … Anyway, she was round a couple of days with her management. She was at that time – this was before The Seekers got back together and did all that magnificent tours they did over the last five or six years, Andre Rieu included.

Judith is a honky-tonk girl; she loves the music of spiritual and going across to honky-tonk, like Scott Joplin, the ragtime, and all this sort of stuff.

Elizabeth: Oh, fun!

Michael: And she had written several things that she wanted the sheet music to be illustrated to sell, as part of the Judith Durham empire. And she did the ‘Banana Rag’. So immediately I did the illustration for her. I didn’t take any payment. I said, “Look, Judith, might I be impertinent and ask you to come to one of my clubs and sing – come to dinner?” She was a very strict vegetarian and looked after herself incredibly well after a terrible accident where she had to look after her whole system and she’s done that magnificently.

So there she was singing, and this was when The Seekers had just released one of their LP’s, called “Morning Town Ride to Christmas”, which was for children’s songs, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the house of these senior gentlemen at the club I was talking about, one of these good old Melbourne clubs, when she sang “The Carnival’s Over”.

Elizabeth: Oh yes.

Michael: Absolutely superb, so that was more than enough payment for doing some artwork.

But since then, I continued … and met the desperate Keith Potger.

Elizabeth: Weren’t you lucky. Weren’t you lucky. Weren’t you lucky to have that gorgeous woman.

Michael: I was lucky. I was lucky. But I had to tell you, Judith - they had an article on her website, and she’s on Facebook as well - had at that time recorded with The Lord Mayor’s Orchestra here in Melbourne. It was called “The Australian Cities Suite”, and she had written a song for every major city in Australia. And I remember she and I were trying to do a book together, a book based on a song that her husband – who passed on through, oh gosh, what was it – the wasting disease, muscular disease …

Elizabeth: MS? Muscular Dystrophy?

Michael: Muscular Dystrophy. I’m sure that must be it.

He put in a song called “Billy the Bug and Sylvia Slug”, and so we put that into a book. And I took Judith along to see some of the heads of various publishing firms in Sydney as well as the head of ABC merchandising in their ivory tower down in Haymarket area. Beautiful beautiful premises they have there, ABC Studios. And so Judith was much heralded in both places when I took her as my guest to introduce this book to her. The book didn’t work unfortunately, but she did start singing in the car as we’d arrived early in the carpark of the ABC citadel in Haymarket. She started singing. And we were all sitting there. And she started singing songs again from The Seekers.

Elizabeth: I don’t think I’m ever going to stand up again.

Michael: So here we are in Kooyong, and there’s the beautiful strains of Judith Durham singing songs, and I thought, “It doesn’t get much better than this.”

Elizabeth: Oh wow.

Michael: I don’t think Deborah Harry could have done the same.

Elizabeth: Do you think Judith Durham would speak with me on this podcast?

Michael: Judith is a very accommodating person, and I’m sure that if you ask through her management, Graham her manager would – I’m sure - she would look at that favourably.

Elizabeth: Would I have to wear a ball gown? I have a couple. To meet the Queen.

Michael: Meet the Queen. (Laughter)

But anyway, I suppose too, in my business – and Australia is not a huge place really, when it comes to who knows what and we talked before about the degrees of separation.

Elizabeth: Absolutely.

Michael: And so, a lot of my stuff has been … involved with, because of my work, a lot of singers and whatever via The Hat Books. I remember Russell Morris, not in this place but a previous place.

Elizabeth: “The Real Thing”?

Michael: “The Real Thing” Russell Morris. Brilliant, brilliant, and had the two LP’s as well.

Elizabeth: And Molly, Molly is attached to that – he produced it, didn’t he.

Michael: Yeah, but Russell Morris had this concept that he came up with his wife 30 years ago. It was about a toy that was pre-broken and you had to fix it. The whole idea of the toy was that you had to re-glue this broken toy.

Elizabeth: Right.

Michael: It was ceramic, and he was so keen on it, but I just didn’t think it was going to work. He was a man with an incredible imagination –

Elizabeth: Russell Morris?

Michael: Russell Morris. He had this toy concept, but it didn’t work, because I don’t think kids want to sit around re-gluing a toy that has been broken. I don’t know what he was on.

Elizabeth: He was quite resourceful.

Michael: Ah, he is. Look at the way Russell Morris has revived in recent times. And he’ll have to excuse me. I don’t remember, but I’ve certainly listened to his two LP’s – albums as we used to call them, back in the old days – that he did. All bluesy and whatever, and he’s still got a magnificent voice.

Elizabeth: You know, there are so many Australians that are not – what should I say – recognized as they should be, I think. And such talent.

Michael: Ah, yeah.

Elizabeth: And do you think we need to go overseas, like in the old day. I was listening to a program last night, actually, and Brian Cadd was on it. Love Brian Cadd. Beautiful, beautiful music. And he said you know, back in the day you had to go to London.

Michael: Yes, yes. Well, look at Easybeats and stuff like that.

Elizabeth: Do you think people need to go?

Michael: Brian Cadd and The (Bootleg) Family (Band), that’s what he calls his group, they are reappearing at – they are doing an Australian tour this month in February – I saw it on Facebook, actually.

Elizabeth: You know, a friend of mine who’s a pastel artist, highly acclaimed – we were talking about this, and she said in this country, she’s just not recognized and she really needs … She’s working in a boutique!

Michael: It is a problem. You know on Facebook, which is one of the loves of my life, you see a good deal of Australian up-and-coming authors and illustrators, and ones that you dearly wish would … And I do believe that you if you earn it, you deserve a place in the sun – your ten minutes, twelve minutes of fame, all that kind of stuff. And if you’re smart enough, after your time has been, you then start doing things which reinvent yourself. I’m not talking about Madonna-style, but I’m talking about coming up with new things, being aware of new trends and seeing whether you can adapt your talents.

Elizabeth: Being a survivor.

Michael: Being a survivor, absolutely. Because let’s face it, and I’m very grateful – for example, the schools around Australia – 45 years…

Elizabeth: I’m sure they’re grateful to you too.

Michael: I go into the schools and there are teachers there that say, “Look, the last time I saw you Michael, was when I was in Prep or Grade One, and I loved your books then and I still love them."

I’m just so thankful.

Elizabeth: How do you feel, other than gratitude?

Michael: Well, this is one of those major things, of feedback you get. And some of them come up and say “I started drawing because of you drawing”.

Elizabeth: You’re inspirational!

Michael: There are just those things there that I … and also entertaining. Doing a bit of stand-up comedy, giving out very silly prizes like Barbie books to Grade Six boys for good behaviour. I know Preppies will never forget those things.

Elizabeth: Can you talk us through – when you present to the school, how do you do that?

Michael: This year I’ve got a ‘Michael Salmon’s Monster Show’ which is talking about more or less the same thing, but some different pictures to ones I’ve been doing before. Essentially what I realized right at the start is if I do some speed cartooning, right in the very first picture I draw there, and do it so quickly in a great show-off manner, you get the kids hooked.

Elizabeth: It’s magic; it’s in front of us.

Michael: Because the little ones, they say “Look what he did! Look how fast he drew!” And I always knew that that particular facet, if you did it correctly, the little Preppies in the front – because we do try to get mixed grades, with the Grade Sixes at the back – is that you would have their attention if you kept on. So I sort of talked about the way I invented characters and how it happened.

Bobo my dog who is not here today – dear Bobo in the book I wrote called Bobo My Super Dog, where I sort of – he saves the world a bit.

Elizabeth: Of course he would. (Laughter)

Michael: Oh, I don’t know. Let’s just go back to the bit about Australia and the people who are trying to make it, and they are doing their very best and you see their brilliant talent. And it’s very evident on Facebook – it’s one of my major purveyors of talent – the ideas that people come up with and all that sort of stuff. I mean, you’ve got some brilliant people here in Australia.

You look at Leigh Hobbs for a start. Now he belongs to the Savage Club as I do, so I catch up with him for lunch on occasions. And there he is with his two-year tenure in his position championing children’s books and children’s literature around Australia. His cartoons are very much like Ronald Searle, the famous British cartoonist, who did the original cartoons that accompanied the original published books and also the film versions of St Trinian’s movies, of schoolgirls and things like that – the naughty schoolgirls. And Ronald Searle was a brilliant, brilliant artist, and he had the kind of nuttiness in his cartooning that Leigh Hobbs had.

You look at Leigh Hobbs’ stuff – they are very, very sparse, great placement of colour, they are done in a very slapdash manner. It all works together beautifully – from Horrible Harriet, to Old Tom and whatever.

And if you’ve got other people – what’s that book by Aaron Blabey – something or other Pug? (Pig the Pug) I bought some books for my very young grandchildren for Christmas, and I thought, “I haven’t seen these books before.” And here he is winning awards and YABBA (Young Australians Best Book Awards) Awards and all this kind of stuff.

And so much talent around. And it’s hard in Australia to make a living as an author, because the royalties and stuff, even if you are one of the top ones, may suffice for a while but aren’t continuing.

Elizabeth: And yet Michael you’ve done that – for 50 years – haven’t you.

Michael: Only because of schools. 45 years in schools and 50 years in the arts. But mainly because I branched out and did things like theatre – the television show. You saw when you first entered the merchandise for 'Alexander Bunyip'. Spotlight stores were behind me for fabrics for a decade, and they finished not a huge many years ago. And that had nothing to do with 'Alexander Bunyip'. But the fact of really, of diversifying.

Elizabeth: Okay.

Michael: And the books for me lay a platform. When Mum or Dad read a book at night to their children, and it happens to be one of yours, and it’s something they like, and they happen to be one of the lead buyers of Spotlight stores and they say “We must do something about this guy”, and they came round and sat where you’re sitting, and they said “We’d like to offer you a deal.” And I thought, “Oh thank you. That’s great!”

Elizabeth: But can I interject? The vital part of that is certainly that there is talent and diversification, but it’s also the ability to connect with people - which you are very skilled at. And the warmth that you have …

Michael: Well, thanks to my mother, because she was a people person. Yes, you’re quite right – it does help to be a people person if you’re an artistic person. Of course sometimes it doesn’t flow. Some of the best children’s authors are not people persons. So you can’t expect to do anything.

I learned long ago of creating an impact on your audience – start and hold them if you can from then on, and then you can impart any message you want. And the only message I really impart to the children is about developing their creativity, for them to start working on the things they’re good at, or keep drawing or singing or whatever it may be.

Elizabeth: I really want to segue into something from those comments about your work for the Alannah and Madeline Foundation. That is so, so pivotal. Can we talk about that?

Michael: Yes. Do you know, in general terms, it’s really good if you’ve had success, I’ve found, especially in the arts, to find venues and areas and avenues to give back to society. I hope that doesn’t sound too corny.

Elizabeth: It sounds beautiful.

Michael: Up here, I’ve got some – when I was one of the patrons of “Life Be In It” for the Victorian –

Elizabeth: Oh yes!

Michael: And I designed – not the vans, those large pantechnicon vans that went around and advertised anti-drugs and –

Elizabeth: It was Norm, wasn’t it. Norm.

Michael: Norm was “Life Be In It”. This was the Life Education Centre, the one started up by Ted Knox at King’s Cross Chapel, but they went to a huge thing. Large pantechnicon trailers filled with the latest kind of things, and all round Australia, but particularly in Victoria – because that’s where my expertise was, helping them design big wheels to go on, painted by local mums and dads. And I also do it to do some fundraising.

But Life Education had a Harold Giraffe as their logo, and it’s still going gangbusters. So these things would go to schools, and like the dental van they locked you in that, and they would see these incredible digital displays of bodies and drugs and anti-drugs, things like that. Magnificent, magnificent.

That was one thing I was involved in. A good mate of mine, a school librarian called Marie Stanley, who’s since not a school teacher anymore – a school librarian – she rang up soon after 1996 when the horrific Port Arthur thing had occurred. She had been seconded – Walter Mikac, whose wife Nanette and two daughters Alannah and Madeline were shot dead – he knew he had to do something. So he went to see the Victorian Premier at that stage, Steve Bracks, and also saw John Howard. And between them he got funding to set up a St Kilda Road office and start the Alannah and Madeline Foundation which is purely there to help the victims of violent crime – the families, the children – provide them with some kind of accommodation or support or clothing, needs, or toiletries – a whole range of stuff there.

So they seconded Marie Stanley from Williamstown North Primary School. Because I’d visited her school many times, she rang me up and said, “Look, Michael, I’m doing this, I’m on salary, but I need your help. Could you help me invent a character?” So I came on board with Alannah and Madeline (Foundation) on a purely voluntary basis, which is my pleasure, and we invented a character called Buddy Bear as a very safe little bear and a spokes figure, whereby – and there are behind me as we speak in this interview – there are Buddy Bear chocolates up there. And they did something like five million chocolates with my name and my design on it through Coles stores and Target stores …

Elizabeth: You know Michael, next time we meet I need a camera. (Laughter)

Michael: That’s just 'Buddy Bear' stuff. And 'Buddy Bear' has gone on strongly and it’s now part of the Alannah and Madeline Foundation. But they got involved in a very important … the main focus of anti-bullying. And I was the person – I want to say one thing, because it’s true – I suggested that they should go – violence and all this stuff for families was terrible enough – but if they wanted to go to the bully, they really should get into the heart of the matter. And to me, I said to them once, “Look, please. I’ve seen what we’re doing. We’ve got Buddy Bear as the spokes figure for violence in the home. But we really should be hitting schools and things with something that centers around bullying and have an anti-bullying campaign.

And you know, it is one of those things which is said at the right time and the right place. And now we’ve got Princess Mary of Denmark who is the international head of 'Buddy Bear' and they’ve got their own thing over there because of her Australian connection with Tasmania. We have the National Bank who are the sponsors of the 'Buddy Bear' program of the Alannah and Madeline (Foundation), so we have a fully-fledged charity. But the early days of inventing 'Buddy Bear', and a lot of people who gave their time and effort for no cost as I did, and pleasure to get the whole thing going. But it was all through initially Walter Mikac, thinking that with his deceased wife and two little girls, he had to do something.

He was a pharmacist by trade and he was a smart man – he is a smart man – and he set the wheels in motion. And so it was a - ‘pleasure’ is not the right word. It was satisfying to be involved with a program that was ultimately going to help children feel better and safe and especially with this bullying thing, of being able to …

Elizabeth: Personally, I love fundraising and I do a lot of it. And actually we have on the agenda this year a fundraiser for another children’s author: Pat Guest. His son Noah, and Noah has Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy, and the family need a wheelchair-accessible vehicle.

Michael: Yes, yes, yes.

Elizabeth: Pat’s a wonderful person. He’s published five books and counting, and has written one about Noah called That’s What Wings Are For. He has actually podcasted with me. So I’m going to put you on the spot now and ask you if you would like to create something –

Michael: Absolutely! Let me know …

Elizabeth: I haven’t even finished my sentence!

Michael: No, no, no, the answer’s yes. The answer’s yes.

Elizabeth: The generosity! Thank you.

Michael: No, no, my pleasure. You talk about the – do you pronounce it ‘Duchenne’? There was a very famous fundraiser with that society up in Cairns several years ago, where various artists and musicians and illustrators were asked to provide – and they said a ukulele – so you had very famous artists and musicians and illustrators creating and painting their own version on this practical ukulele that was sent back to Cairns and auctioned off for charity and raised a whole lot of money.

Elizabeth: You know Pat, I think, would love to meet you. And I know Noah – the whole family are just beautiful people.

Michael: But I’ll have you know, only because of that connection where they contacted me saying “Would you like to …” and I had no knowledge whatever of the disease and the toll it took.

Elizabeth: I’ve nursed a couple of boys with it.

Michael: From my recollection, would it be quite correct to say it’s quite gender-specific? It hits boys more than girls?

Elizabeth: Yes. The two children that I nursed were brothers, and they passed.

So we want to focus on the positive side, and this Saturday, actually there’s a trivia night which is sold out –

Michael: Oh good! Good, good.

Elizabeth: And it’s Eighties music which is my thing – I love that – so hopefully I will win, everybody. Don’t bet on me, Michael, but if there was a ticket, I’d invite you. But we’re looking at later in the year and we have some great people. Dave O’Neil wants to do a spot –

Michael: Oh yeah, good, good, good.

Elizabeth: And he podcasted with me. And like yourself, pretty much before I got my sentence out, he said 'yes'.

Robyn Payne whom I wrote my song with for my children’s book – she wants to write a song. So we’ve got many … and Robyn Payne was in Hey Hey, It’s Saturday for many years. She was in that band, and Robyn’s incredible – she plays eight instruments.

Michael: Right, right, yes, yes.

Elizabeth: She’s performed at the Grand Final; incredibly talented lady. I just ran into her the other night with Neil, her husband, and Steph who’s a good friend of mine and recently performed with her on stage as well, they’re looking at writing a song for Noah. So it’s taking off.

Michael: One of the best fundraisers I’ve been to is a yearly event – still going – the Alannah and Madeline (Foundation) did. I don’t keep in contact with them directly; it was just a pleasure to work in, but what they did at the Palladium Ballroom – have 'Starry Starry Night'. Now 'Starry Starry Night' would have almost anyone who’s anyone in show business, on television and the media, would be there, from the jockeys at Melbourne Cup who would be singing Village People and whatever. Quite brilliant. And they had a huge host. We’re talking about – and I’m not exaggerating – 50 or so celebrities attended that. Black Night night and it really was a “starry starry night”. I haven’t attended for a long time, but I did my duty and it was a great pleasure to be there and part of it. But that was a brilliant fundraiser, and still continues as a fundraiser for the Alannah and Madeline Foundation.

Elizabeth: Oh, I’m so honoured that you said yes to me before I even finished my sentence. Thank you so much!

Talking about stars, I’d like to go to my signature question, and then we’ll say adieu to you.

Michael, this is a signature question I ask all my guests: what do you wish for, for the world, and most importantly for yourself?

Michael: Well, as we’re sitting here in early February of 2017, because of all these incredible events that are going on every quarter of the day from the United States there, where the world order seems to be rapidly changing, and oddities occurring there and without going into it too heavily we all know what we’re talking about, I have a hope that the situation in America remedies itself, and that the situations change rapidly, and that America gets back, because as the biggest country in the world for what it is and known as, because we need the stability of America etcetera, so it’s a fairly direct sort of wish that America gets its act together again soon, and maintains something that we can trust in. Because America really is being that main country in the world.

Elizabeth: Do you see a way – does that start one person at a time? Is that how things start to change?

Michael: Gosh, as we’ve evidenced with the Women’s March and a whole range of stuff now that the immigration – oh dear – it just goes on, goes on. And without going into a full-scale discussion of that, my wish is that America gets back together quickly, and maintains and gets someone new in charge. I don’t know how that’s going to happen – impeachment or … but something has to happen, so that the world can feel stable again. And that’s not grandiose, but that’s probably affecting a lot of people in the world. As every new edict or special signatory thing is signed in the White House, the ripples it sends across for instability is quite amazing. We’ve never seen it before, unless you were there during Chamberlain days when Neville Chamberlain was talking to Hitler, and some of those – not grandiose or high-flying stuff, but it does affect especially Aussies who love America dearly, and America loves us.

Elizabeth: But to me your books so beautifully reflect history.

Michael: Some of them do, some of them do. It’s like a Facebook page – I really do love entertaining people and making them laugh. And that’s probably the last part of your question – I really would like every child in the mass audiences I encounter, we’re talking about 500 or so - I would like to think that every child had an opportunity – not because of anything to do with my talk that may be instrumental , it doesn’t really matter – the children of today can reach their potential, and the energy and the talents they have are recognized. Not squashed, quashed, forgotten, put to one side by society or families, issues, whatever it may be.

Elizabeth: You know, that reminds me of a good friend of mine, Andrew Eggelton. So Andrew Eggelton is an interesting man – he’s a New Zealander actually; he’s a Kiwi – and he believes in the Art of Play. So his wish is that everybody gets to use their God-given talents.