Episodes

Monday Jan 23, 2017

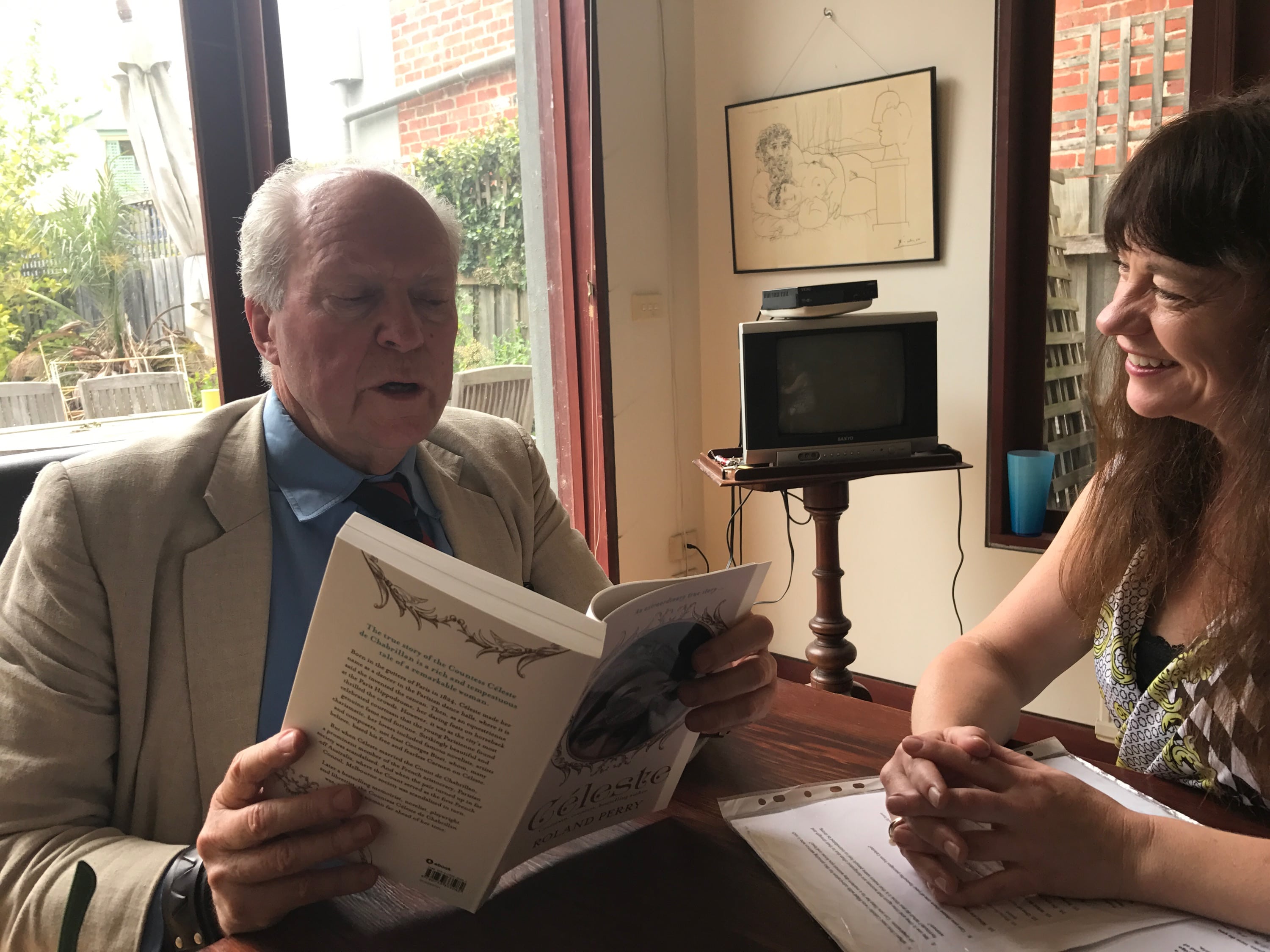

Episode 5: Interview with Professor Roland Perry, OAM

Monday Jan 23, 2017

Monday Jan 23, 2017

Prolific author and former journalist Professor Roland Perry talks to Elizabeth Harris about:

- His latest book, Céleste, the story of the Parisian courtesan who rose from poverty and abuse to become the comtess de Chabrilland, bestselling author, and actress.

- His observations of the changes in the book publishing industry over the past 40 years.

- The time he turned down a seven-figure sum to write a biography of a high-profile sports personality.

- What it means to redraft a manuscript.

- The role of a professional editor.

Listen to Roland Perry read the opening prologue chapter from Céleste.

Find out more about Roland Perry's work at RolandPerry.com.au.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Elizabeth: Welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris, the show that connects authors, songwriters and poets with a global audience.

So I can continue to bring you high-calibre guests, I invite you to go to iTunes, click Subscribe, leave a review, and share this podcast with your friends.

I am delighted to introduce the charismatic and dashing Professor Roland Perry. Professor Perry began his career as a journalist for The Age newspaper in Melbourne. After five years in England making documentary films, his first novel, Program for a Puppet, was published in 1979. This international bestseller was translated into eight languages.

Educated at Scotch College, Melbourne, Professor Perry has an Economics degree from Monash University. His awards include the Frederick Blackham Exhibition Prize in Journalism at Melbourne University (1969); the prestigious Fellowship of Australian Writers National Literary Award for non-fiction (2004) with Monash: the outsider who won a war; and Cricket Biography of the Year (2006) from the UK Cricket Society for Miller’s Luck, a biography of all-rounder, Keith Miller. In 2011 Professor Perry was made a Fellow of Monash University. For his service to literature he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia. Monash University bestowed a Professorship on him in October 2012. Professor Perry is the University’s first Writer-in-Residence, lecturing PhDs and PhD aspirants on all aspects of writing, and Australian history. He also teaches writing classes in Presbyterian Ladies College Melbourne’s Gifted Education program.

I’m thrilled to announce that today we’ll be featuring Professor Perry’s 30th book Céleste, the biography of the strikingly beautiful woman who in spite of her challenges, rose above poverty and abuse to become a countess.

Professor Perry, welcome to Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris.

Roland: Thank you Elizabeth Harris.

Elizabeth: You’re most welcome. Roland, we first met at your book launch for your magnificent book Céleste. It was such a fun night, complete with a brilliant performance of the can-can by dancers from the Edge Performing School in Eltham…

Roland: Not me.

Elizabeth: Oh you should have joined them, Roland.

Roland: Oh beautiful.

Elizabeth: You were interviewed by the delightful actress Natalie Heslop, and of course the irrepressible Meera Govil, owner of Eltham Bookshop here in Victoria, Australia, hosted the evening. Please tell my listeners about your latest book, Céleste.

Roland: Well, you started off by saying that she was strikingly beautiful. She was a courtesan. She started life … had a bad start. She had two abusive stepfathers, one that had beaten her mother up in Paris, and the other had tried to rape her, probably successful as it was very hard to tell from the memoirs. So this isn’t a good start. She ended up on the street, running away from the second stepfather because of the abuse, and the mother, interestingly enough, which is very rare in a way, she sided with the lover because he was the breadwinner.

Elizabeth: Extremely disappointing.

Roland: And this upset her, as it would anyone if your mother abandoned you or a man tried to rape you, whether you were male or female, that would be pretty rough. So she ends up on the streets, meets a prostitute, and then caught by the police. The police put them both – put her in prison, the famous prison in Paris. And there she meets another woman and has a lesbian affair with her, and she says “When you get out of this your stepfather will still treat you badly when you go back.” And she’s predicting …The girl was only 16, and Céleste was younger, and this happened to be true, and the woman had said, “When you get out, come to a brothel. You will meet really rich men. It will be much more exciting.”

Elizabeth: Goodness.

Roland: So she fell for that, and she did visit this person. And the person said come to the brothel, and she was in the brothel for one year. And she dreamt of meeting someone from the upper class. She used to go to the theatre; she loved the theatre … she used to go to every afternoon matinee … she just adored all that. And she would see all these beautiful men and their beautiful carriages and the beautiful women arriving at the theatre and she said, “I want a bloke like that.” Essentially. French don’t use a word like ‘bloke’. She said “I want a normal comme ca”, and she did meet many of the upper class in the brothel. But they weren’t nice to her; they were abusive in another way. They were condescending and patronizing and treated them a bit like meat. It wasn’t a particularly good experience for her, particularly a poet called de Musset who was a lover of someone called George Sand, a female ‘George’, a famous French writer and poet at the time. He’d been rejected by her, so he went to the brothel and abused all the prostitutes there, not physically but mentally – he could be very brutal with them – and Céleste copped a bit of this.

Elizabeth: She stood up to him, didn’t she.

Roland: She did, as she handled him pretty well.

Elizabeth: That’s fantastic, I loved that scene.

Roland: One of the things I found is people ask “How did you get all this information?”, and well, she wrote five, maybe six, sets of memoirs. I had access to the five. I haven’t bothered with the sixth set which only came out very late last year.

Elizabeth: Can I ask how you gained access to those, because it’s very interesting.

Roland: It’s very easy. It’s been an easy book on one level. Primarily you go to all the libraries in France, and one or two of the books are at the Latrobe library in Melbourne – they’ve been there for a hundred years. But a lot are published in French, and a couple have been translated, so you have sources of not all of them. So if you rely on one – say you got the American edition and the French translation – look out. You’ve got nothing on Australia in it.

Elizabeth: Can you read French?

Roland: Yes.

Elizabeth: Wow.

Roland: Badly. I can read it with a dictionary.

Elizabeth: And are you fluent?

Roland: No. But I did do some of the translation myself because I wasn’t sure of the meaning. I wanted to go through the meaning myself, and then talk to a top translator. That was in Thailand, a French woman, and she lived in Thailand, so that was really useful. A top translator there, and I acknowledged her in the book as well. Because we really mulled over the meaning of ‘accost’ or ‘rape’ or ‘abuse’.

Elizabeth: Would you like to mention her name now?

Roland: I don’t think we should do that, no.

Elizabeth: Okay.

Roland: I have a good relationship with her, but I don’t think she would appreciate that necessarily.

Elizabeth: Sure. It’s because you said you’d credited her in the book, so I wondered…

Roland: I did acknowledge her in the book, so she gets a bit of acknowledgement there.

So that gets you access to all the material, so the rest of the time you do it yourself. You get hold of translations, you go into libraries, you get the English version of them, and this is the problem: the English versions are sometimes very bad versions of them. And then if an American translates, you get big chunks left out that might be of interest to you.

If a French person translates, you’re going to get other bits of ... And the whole Australian section is very badly handled, so I was fascinated by that, and it turned out by the luck of the draw, that the Australian connection ... not ... at all. And I thought, how am I going to make the Australian bit interesting – it didn’t work out that way at all. So that was a bonus. So the source material’s too much.

I mean, if you’ve got five sets of memoirs all running to 80,000 words and you’ve got to go through them all – I didn’t go through them all because some of them were repetitive and didn’t need to. And she was a dramatist – we haven’t come to that part of the story, of course, but she ended up a writer. So whenever she wrote anything it was over the top sometimes, and you had to pare back some of the commentary, because it was just too dramatic. However she had integrity and you can work that out by checking the things that were going on around her and that she commented on. So there are ways and means and I’ve got a lot of experience looking at work and thinking “Is this person giving us the truth?” I think on about two occasions, maybe it was just an error on her part or one of the other part, I thought she was gilding it a bit. But otherwise it was frighteningly honest about herself and her partner, the one she married eventually. She loves a man and then she tells you what his real foibles were, and that’s quite exceptional. You might as well hide those things, especially if they’re still in love, even if they’re dead.

Elizabeth: Exactly. Does she go into details?

Roland: He picked his nose, for example, I’ll tell you that.

Elizabeth: It’s a brilliant book and I certainly enjoyed it.

Roland, you’ve written so many books – 30 in all, including 16 biographies. How do you decide what to write about?

Roland: Yes, I think about that one. First of all, you’ve got to feel something for the book. I’m not on a hire. I’ve taken two, I may take a third commission – it’s been dangled in front of me. Of the 30 books, ten percent publishers have come to me. Publishers often come to me. Many times a year I’ll get an offer of some sort. It’s beginning to fade now because I have my own agenda of books. So occasionally a publisher comes with a good idea and I feel I could cope with one or two.

If you don’t feel enthused, there is no point even bothering, because you could always do something else that would earn you as much. It’s not a matter of money; it’s a matter of how you want to approach life, if you’re bored witless by a subject. I got offered a seven-figure sum, eventually, for a sports biography. Not by an Australian, but by an American. They got in touch with Bradman who was one of my subjects, and they said “Can you get to it?” and then Donald got in touch with me and said, “Look. The figure kept going up through a middle man." And I just couldn’t face the subject. A, I wasn’t impressed with the person, and the sport was not impressive to me.

Elizabeth: Well, that shows your integrity, doesn’t it.

Roland: Well it does, but there was also some madness there. I wondered why they were so keen to get a book out. It was a bit of a rush, and it turned out there was a nasty biography being written about the guy, and he wanted a PR one done. Now I’m not into doing other people … I won’t do that – I won’t have PR lawyers hanging over. I won’t do a biography for someone. I just won’t do it, because the whole feeling is emasculated – the whole character is emasculated by lawyers and things standing over you. I won’t do it. Unauthorized only for me; all of them have been unauthorized. Some have been dead, so I didn’t have to get their authority. The other thing is I have my own agenda.

I want to be turned on by the book. You can all think of things you want to write about. Might be needlepoint, and don’t laugh, because one of my axioms is “There are no dull topics, only dull writers.” Listen all academics out there – listen hard. So those are the sources, my own agenda. A couple of times, I’ve been thrown a book, not by a publisher – the idea, I should say. And it’s been terrific, and this is one of them. One of my best ones was Tim Burstall, film director, and in 1990 (I reckon it might have been earlier), he said “I can’t get this up as a movie role. Would you like to have a look?” And Tim was very gracious that way, but the point is, that when someone with his intellect – and I did not meet a brighter soul in Australia – he’s a bit of a rogue – not everyone loved him. It’s split down the middle: men and women, he was a rogue, but he had a wonderful mind.

Elizabeth: But that’s part of the attraction.

Roland: Just the mind was fantastic. And I thought, I’ll just have a look at this if Tim says it’s worthy. And when I did the research, put a proposal, I thought it was worthy.

Elizabeth: Because it does sound like at points it was laborious, because there was so much information to plough through.

Roland: No, not really.

Elizabeth: The time factor, you enjoyed all that?

Roland: The thing is that, had I written it when he’d given it to me, I just wasn’t equipped. With my first biography, it was overwhelming. I did try to get a publisher 9 years later with it in France, and the agent, without reading the book or the acknowledgements, pilloried this whole idea. Fair enough, rejection is part of the business.

Elizabeth: But you had a sign, Roland, didn’t you, I was reading – it was really interesting.

Roland: Well yes, I had a providential moment. It’s a lovely tale, and I’ve lived on it because it really got under my skin at the time. That’s why - you remember these little slights.

Elizabeth: You do, you do!

Roland: What happened was, I went to this agent who sold with the French market with another book earlier in my career, a few years earlier. I must excuse the French on this, but she wasn’t French. She was American, but she’d been living in France 40 years, and she was a bit snotty. So I love her for getting me sold before, but I wasn’t happy about this moment. So I went to her apartment office in a beautiful place next to the Eiffel Tower. She had a look at it (I’d sent it in the post) and she said, “Look, La Belle Époque period has been done to death, and who cares about the wildness of Australia.” And I had no answer to that, because I didn’t even know it was called La Belle Époque. As it turned out, it’s not La Belle Époque – she got that wrong – La Belle Époque was 1890 to 1910, really parallel.

Elizabeth: Have you let her know that?

Roland: It’s a bit late for revenge. Time is the revenge on this – time. No, time is the revenge because I was determined to do it. No amount of publishers … You see, to be brutal, I would back my judgment against any publisher that I met. How’s that for arrogance, but I would. Doesn’t mean I’m right, but I back my judgment. And I have close friends I would present books to who would say yes or no, and I don’t know their friend, so I don’t begrudge them. It’s “silly old bitch” or “silly old bastard”.

Elizabeth: You might need a swear jar for Samuel Johnson’s “Love Your Sister”.

Roland: You have to have confidence, and you gain confidence. I’ve done 16 biographies and no one else has done that. Unless the publisher knows what they’re talking about, it’s going to be difficult to put me down on a really strong subject. And there’s one publisher I had, she’s like a brick wall. We often laugh, and I say I’m not going to be bothered scaling this wall.

Elizabeth: You’re a wise man, Roland.

Roland: And here’s another one. I put up a proposal about 6 years ago for a book, and the publisher – they all remain nameless because some of them are good friends – he said, “You are only going to sell 20,000 copies and you want a lot more than that and we can’t pay you all that much” and blah, blah, blah, I was only going to sell 20,000 copies. And I thought, well that’s a bit rough, I thought I was going to do more. What they do now is even if they are very intellectual publishers, they will go to the marketing people, and the marketing people go, “I’ve never heard of him. I’m not interested.” And it’s sales people, and they don’t think or read, a lot of them. Now that’s abusive to those who do, I’m sorry, but sales people, they’re not that interested in content.

Elizabeth: And they read.

Roland: Well I’m not sure. Publishers don’t read. They farm them out, and get a view on it. A lot of them are big factories now.

Elizabeth: Shame, isn’t it.

Roland: I don’t get nasty about it, because that’s part of the way it’s developed, and the sales people have sort of taken over. What happens is, if a publisher gets a bright idea and goes through with it and it fails, all the sales people are disgruntled and all the retailers won’t take this and it’s a chain reaction of negativity. There’s the old style of publisher which says “I’m publishing Elizabeth’s book; it’s magnificent and I don’t care about anything else.”

Elizabeth: Thank you.

Roland: They’re not there anymore; they’re all battered down. I’ve known publishers who’ve been like that – very single-minded and good about their choices.

Elizabeth: Why has that changed? What is going on?

Roland: The marketing has just killed it. If you think, when I was first published in ’79, there’d be a thousand times more books being published than today.

Elizabeth: What a shame.

Roland: Someone said to me, there were a hundred times more books being published in ’69 you know. So now it’s just a great mass of books being churned out – a lot of rubbish of course, very single-minded market-directed work. And look, if I was a publisher – I’ve thought about this often - I’d hire a couple of writers who are known for big-selling books, but are good writers, who are known for their personality – you do that to generate money to give the good writers a chance. So there’s nothing wrong with the money in that respect, but you’re battling that all the time.

You go in no matter what your reputation or sales record, they’ve never heard of (you). Say Monash. That sold very well and I came out of the blue with that and the publisher, on the strength of my cricket book – she’d been publishing cricket books but I’d done a lot before that – this publisher said “We’ll back your judgement on it.” And there was no reason to do Monash. There was no particular issue in 2004; that’s just one example.

You’ve got to push your idea forward; it’s an intellectual battle at one point. If you don’t get in front of people, the sales people make the decision, you don’t get a run

Elizabeth: Do you think with all the e-books that have moved online, it’s now easier to get your book out there?

Roland: Well I’m sort of established with the old school and I see everything trending the e-way, but it’s still not a huge percent of your returns. I’d say 5 to 10 percent of what I earn is e- at the moment, and I’m not sure it’s trending so heavily. People are swinging back to the old…

Elizabeth: Sorry; when I say ‘your work’, I mean new writers. If publishers aren’t particularly interested in you, is that one way of doing it?

Roland: Oh, self-publishing and putting it out there. Well I think it is; you can, but if everyone’s thinking that way, there would be more writers than readers, because what happens in a publishing house is a function, an editing function which keeps the work readable. And most people don’t know how to write when they start.

There are a few naturals. Even the naturals – there are very few of them, very few of them – and there’s no background that gives you an advantage over others. Graham Greene came out of journalism. Le Carré came out of the Foreign Office; his elliptical style; he was a spy and he writes accordingly. He was elliptical and his biographical detail is almost diffuse. Part of the narrative is complicated in that way.

So there are no rules, but if you don’t have an editor to say “Well chum, that’s very nice to be wonderfully esoteric, but I don’t know what you’re talking about.” And that’s where academics fail in this country miserably, because they peer review – to get a Ph.D., you don’t have to be in the public domain with the dirty unwashed who read. They might be very bright, but they’re dirty and unwashed, and the academics say “We’re not going to have those idiots judge my work; they’re not going to buy my work – I’m superior.” And what you’ve got now is a third-rate academic work coming out – I have to say that – third-rate. The French don’t do that – it’s not peer reviewed - you have to publish in the public domain, have the great unwashed read you, buy you, and understand you. Same in England and US.

When you’re peer reviewed, that means I get Elizabeth’s work and I know Elizabeth well, and I’m going to give her a lovely review. I can’t understand a word she said; she’s a bloody awful writer. And you review mine and say “It’s a terrible book. I like him, but I’m never going to…” So peer review has robbed the nation of two or three generations of real work, because they learn “Oh, you don’t understand that esoteric paragraph, that esoteric chapter? You don’t know why I’ve put in 2000 words of a quote in one line?”

Elizabeth: So all the ego stroking is ruining the industry, you think.

Roland: Oh absolutely. And look, they don’t get income, so they don’t care. As long as they’re published, that’s part of the deal. And they get lots of drafts from within the university. They’re never tested in the … the real test is out there. It’s bums on seats. It’s bums in front of books. And that’s it.

And I’ve never, I’ve never applied for a literary grant – I’m the only professional writer that can say that in this country. Never ever applied for a grant. I’ve applied for prizes if they’ve been put up to me and so forth, if you’ve had to write something down, but never a literary grant from the Government. And that’s because I think you’ve got to earn it, and I know that’s brutal. Cruel.

Elizabeth: I want to get back to when you knew that you wanted to be a writer. What was it that …

Roland: I was working on the newspaper and I was not meaning to – it was a passing point on the way to being a stockbroker. Had no interest whatsoever in writing but I really enjoyed working on The Age. And I was in the business section and thought I’d be there for a while, and there was an editor called Les Carlisle who has written a couple of fine books, one called The Great War, another called Gallipoli. And he was my editor and he was pretty tough, but he was really a wordsmith. And he would look at your work and say “good”, “bad” or “ugly”, but every once in a while he would say “That’s good”. And even within the business section and other sections I began to do interviews with characters, so I got a little bit attached to what was developed. Didn’t know it at the time.

I used to listen to all the other journalists who were ‘gunna’s: “I’m gunna write this great book.” One or two would say “I’m getting married next year and I’m going to have to stay on the paper and I can’t write the book”, and “I’m joining a PR company in the oil industry and I can’t write that book”. And everyone’s talking about writing books and no one’s doing it. I went and lived in England and had a crack. I was reasonably gifted in the language – I wasn’t necessarily gifted as a writer, but I developed; I worked awfully hard. I was probably behind the eight ball a long way compared to, you know, the established writers, and I worked very, very hard and wanted to do it badly. Working and redrafting.

Look, in those days, if you did four drafts of a book, a draft was: throw the manuscript in the rubbish bin and start again without looking at it – that’s a draft. William Goldman, who wrote The Maggots and other books and got a Nobel Prize, he wrote 14 drafts, which is insanity. Le Carré, whom I think is the most gifted writer of the last half century, wrote 6 drafts, and I was brain-dead after 4 or 5. It really kills you. Now there’s a computer technology that allows you to play a bit more, but in the end you have to really go through it and “Is it worthy? Does it work here?”

Elizabeth: What skills do you need other than tenacity?

Roland: You learn, because editors say “Do you really need that character?” or “I like that character; you should flesh it out.” I’m talking fiction now, but it may apply to non-fiction as well. So that’s where an editor comes in.

Most people who get up on the blogosphere and think they can write, well, you see the standard of English slipping enormously, because they’re sloppy. And I’ve seen some journalists do it, thinking “I’ve got to be cool now in the blogosphere”, who trained to write. It’s weak. All book publishers need good editors. If I was publishing myself, I would hire an editor … and I’ve got 30 books on the board; I know what to do.

The difference is that there’s not that much difference in the skill level; it’s knowing what to do when you get to the end of the first draft. I know what to do, be it fiction or non-fiction. If you’ve not been through it, you don’t know what to do. “Is this good? Is it bad? Am I kidding myself?” Narcissists of course can’t be told. There are a few of them writing books, and I was reading one over the weekend – they shall remain nameless – he’s not sold a thousand books in his life, this bloke, in one edition. I’m not being mean – I don’t know him very well, but I know his book sales, and the publishers all bitch about him and the retailers hate him, because he keeps getting published and he sells 800 copies. He’s done about 30 books and the reviewers all love him. They say “It’s just the best book ever!” but it doesn’t sell. It’s like a cricketer who’s got the best strokes, plays a great game for the District team, gets in the State Test team and just falls.

Elizabeth: Who or what is your major source of support?

Roland: Well, I have income, so that’s my major source of support. No, writers should be on their own – it’s not like working in an office – it’s not like having a technical assistant – you have a laugh and you go for lunch. You’re really on your own. You’ve just got to block out your mind. I’m a natural extrovert. I’ve learned and trained – there’s an excuse for that.

I didn’t realize you have to be a real introvert to write. I mean, there’s no way around it. You just got to block out that time on your own and write. And when you don’t have the confidence when you start off, or you’re dreaming and you think “I’ll never have a career in this”, it’s very difficult because you don’t know where you’re going with it. But Le Carré for example, married his editor; that helped. He sadly took off.

Elizabeth: Did they stay together though?

Roland: Yes, that was his second wife. I’ve said too much. You’ve got to like being with you.

Elizabeth: You have to like yourself.

Roland: And I have little friends. I have the television. I can work with the television on. Because as long as it’s not football or something you have to watch every second of, I can have music, I can have lots of things in the background.

Elizabeth: A little bit of background.

Roland: Yes. Training on a newspaper helped, because it’s just absolutely chaos around you all the time. It was when I was there. So you learn – you just have to deliver…

Elizabeth: You have to zone out.

Roland: Yes, gotta zone. So you asked the question – there’s no support whatsoever, and if you’re relying on that, from a muse or wife or partner…

Elizabeth: You’re in trouble?

Roland: … You’re not going to make it.

Elizabeth: Roland, you’ve had wonderful success throughout your life. What does being successful mean to you?

Roland: It means living and doing things that I want to do.

Elizabeth: And what would they be, might I ask, or are we not allowed to know?

Roland: The whole thing is: If you love your work, that’s the reward; that’s my success. If you love your work and you’re living by it – half a century approaching – I mean, I’m 68…

Elizabeth: You’re ageless, Roland, so stop worrying about it.

Roland: I know. So I’m on the verge of 69 with 2019 approaching, it’s been 40 years since ’79. And it started before that: 3 years, 4 drafts, 30 rejections both sides of the Atlantic. I went through it. You’ve got to learn to wear that and learn from what they say, if they say anything. And that gives you clues on what you have to do, and redrafting and learning is part of it. And if you can’t take a rejection, it’s not the business to be in.

Elizabeth: What kept you going?

Roland: The dream of living off it. I used to say I wrote the book called Buying Time, because I had to buy the time to get the work done. I have all the time now, and I focus on the books first and everything else second. So that kept me going – that really was the drive. And look, to have that life and do … I was born to do it, because I enjoyed it so much and I wanted the challenges of more books. It’s an agenda I have. It’s not just about writing till you … with a typewriter. Sometimes books pop in from left field, but I know where I want to go with the next 20 books, vaguely.

Elizabeth: Very focussed.

Roland: You know where you want to go with certain kinds of books, and I jump around the genres. But as I said before at the beginning, it’s writing about things you’re passionate about

Elizabeth: When I first read Celeste, I was filled with admiration for this amazing woman who is such an inspiration.

Roland: We didn’t talk much about that early on, did we? I got sidetracked.

Elizabeth: That’s okay. We can talk about it now. Can you liken her to a modern-day woman you know and love? You can keep it anonymous.

Roland: No, I’ll say who it is, but if Mary hears this, she’ll make the audience understand that she was never a courtesan. This is probably arguably – I’m biased but I’ve worked with this woman and I know how absolutely brilliant she is. Her name is Mary Finsterer. She’s now the Chair of Music Composition at Monash and was a Fellow with me there, but I knew her a long time before that. She is the most creative and prolific operatic composer we have, not appreciated all the time because she’s a woman and has to fight through the barrier.

But I admire her … I’m very good friends with her husband so I’m close to both of them. They’ve got two kids and they’re doing all the family thing. He’s a photographer-cum-digital specialist. He’s very good at his work, creative as well, so you’ve got two creatives trying to get through in middle-class Melbourne. She’s naturally brilliant and if she’s got the time I spend on my books, she’d rocket to the top, but it’s much harder for an operatic composer to make it, you know. Where do they get the income for it; it’s not convention. It’s like being an actor; it’s very, very hard to be top line. And she’s top line and genius and she doesn’t even know it.

Elizabeth: Have you told her that?

Roland: I have in as many words, but I haven’t trialled it on for her; she knows I appreciate her work, and she’ll be a huge name in the next decade, I’m certain of that. But it’s been such a struggle, it reminds me of Celeste, the question you asked: someone uber talented, I would say more talented than Celeste, but Celeste learned – if you read the biography as I did, you’ll see you learn to write. It doesn’t just flow out of your fingers. It just doesn’t work that way; you have to work at it and hone it.

Elizabeth: You do.

Roland: So Mary Finsterer is the one; she’s an operatic composer and she was certainly never a courtesan. She’s certainly very attractive, and I see her as a good friend, and I’ve done a few things at Monash, big productions, right, with big audiences that come along. And she’s so inside her work and her family and she – it could be Barack Obama saying that beautiful thing, and she’d be “Did he?” and get on with her work.

Elizabeth: And it also depends on the filter with which you look through life, you know.

Roland: Yes, but I think when you get someone on stage like that and she’s conducting her own music – and I can show you one of the performances we did – I narrate and she did the music. Things like organizing a small ensemble, and she had two days to practise with an ensemble she’d never met, and the music was absolutely brilliant. And things like – I’ll give you an idea of her genius – so Chopin can be a little bit droopy – some of this stuff is just not for the current audience. And I said to her “That Chopin piece you’re going to do is a little bit awful; there’s something not there – it just doesn’t pulsate”, and I was trying to articulate. She said “I’ll fix that”. So she went and rewrote Chopin, and not one expert in the audience ever said anything about it. She said “How do you like it?” And I said, “You’ve made it live.”

She’s a genius. She needs full-time. I’ve done what I could to help her career, too; I’ve done what I can, because I realize talents need to … You often find creatives are … It’s an emasculating, enfeebling thing, often, because you’re really wanting to do the arts side of it, whether you’re a painter, an actor or writer or composer, really you’re not built for this world, for making this art. So someone wants you to do a business deal or he or she wants to sell something, they’re a bit weak at it because they’re focussed on other things

Elizabeth: We see time and time again that women are denigrated often due to their strength and fortitude. What is it about some people that they are intimidated by strong women?

Roland: Well I really can’t answer that because I’ve had a strong mother – not a tough one but a bright one whom I respected and liked, and I had a really intelligent sister. All the deals that have been made on my books, I would say 70% of the deals on my books have been dictated by women in my career, so it’s very much a women’s business now, particularly judgments on my work. And I worked on a newspaper where the women were equal at the journalistic level. They were equal at the pay level I think, because there was A, B, C, D grade, but the management was all male. So they didn’t necessarily get the plum jobs; I don’t know for sure, but I think so. I was with Michelle Grattan, people like that. I think Michelle was ever held back because of her sex. So the paper was hierarchically male but in publishing, it’s hierarchically female-dominated world now. Even in the film industry, the dim-witted producers throw the manuscript or the script to the secretary, the female, to see whether she’s interested in it.

Elizabeth: That’s interesting.

Roland: Oh yes, I’ve heard that often. So I’ve never come across it that much. That sounds like a very isolated world … but I’ve never felt an insecurity around women.

Elizabeth: And you tell me you love women, Roland.

Roland: Er yes, I don’t think I’m a misogynist, let’s put it that way. I do like the company of women. The same conversation - I have many blokes around the world and they are good mates and I enjoy their company. But with women I can really have a conversation; I can communicate. There’s a yin and a yang on character and things, and even though I won’t go and take a note on what Elizabeth said or what a girlfriend said, but it sticks in there. That’s the female … and women have a sixth sense that men don’t have about character.

Therefore if you want to develop as a character writer, you have to indulge all that and learn. You don’t take notes. You don’t go and do a Psychology course. That’s an intellectual failure if you go and do a course to learn about people. You’ve got to understand people yourself. So women in my life offer that: discussion and communication and all that. Does that make sense?

Elizabeth: Absolutely.

Roland: I do like beauty – I don’t appreciate conventional beauty – I’m not a model-ly type of guy; I don’t like models. I like Ivana Trump or whatever the wife is. I think she’s charming, but that’s not what I’m attracted to.

Elizabeth: So who do you consider stunning or beautiful?

Roland: I don’t look upon her; I just think she’s a beautiful character who’s attractive. There’s an actress who’s been put up who’s a very conventional blonde, for a movie that I’ve sold the rights to – I don’t want to be too definitive about this – and I have another actress who is perfect for the part, who is not as stunning, but is attractive and right for the part. But this goes back to the market dealing; the publisher won’t even … they won’t put her up. I’m the co-producer and I may at some point put this female in front of them. But they won’t get the blonde bombshell because she’s going to cost too much.

But my idea of a ... is a better actress. She’s not a star – she’s just interesting looking and she can act. I mean, she’s good looking but she’s not a conventional … I’ll tell you about what’s interesting – I did a book on Keith Miller called Miller’s Luck, and he had an affair with Princess Margaret when she was 16. She started the affair; he was married and 28. That’s all in the book. And I had to look at the photographs of her and her sister to choose a photograph, her sister being the current Queen. And this is my idea of physical beauty which comes into vogue – I thought the Queen when she was younger was actually more interesting looking than her sister who’s the glamour puss, who mixed with Hollywood. Now the Queen had a big mouth which was unfashionable; she had a really large mouth. And Hollywood said that you have to … The classic example is Jane Fonda. She was flat-chested and they said “You’ve got to have boobs; you’re not getting anywhere even if Henry’s your father.” She said “Alright, I’ll have boobs”, and they said “We’re going to knock your back teeth out” – it’s all in the biography.

Elizabeth: Oh my, that’s brutal.

Roland: Back teeth have got to be removed so that you pull them out and it tightens more. And you look at the Queen and her sister – the Queen has a bigger mouth –her mouth now would be really sensual and attractive. And I liked big mouths then – I was very unconventional. And now women go and put a million dollars’ worth of silicon in their mouths, and in Asia, the women naturally have big sensual lips. That’s how I look at sensuality. That’s an exaggerated example but it was fashionable to have a small mouth and big breasts, and that’s why Jane Fonda went to live in Paris – she couldn’t stand having her back teeth smashed.

Elizabeth: I’d like to move from Jane Fonda to your book if you have time, because you are going to lunch. Is that okay? Would you like to share one of your favourite passages from Celeste?

Roland: Yes. It’s the opening prologue chapter – Young Queen of the Demimonde. For those who are not aware, the demimonde is the underworld, the half-world, the artistic world that is created in Paris. So this is Céleste meeting her future husband, and it’s a very interesting moment. I think it’s the seminal moment in her life, both their lives, because they are really built for each other, as it turns out.

When Céleste Vénard strode into Paris’s Café Anglais in the winter of 1846-47, heads turned almost in unison to stare at this most celebrated beauty, the City of Light’s most sought-after courtesan. The more discerning onlookers searched for imperfections but could find none in this 22-year-old femme fatale. The popinjays at the café were struck by Céleste’s sensual face: the large green eyes, her petite nose, full ruby lips and alabaster skin. Her light auburn hair was long and combed back over neat ears so as not to hide any of her exceptional features. Her full figure did not need the corset under the red dress, which only served to accentuate alluring proportions of lush breasts, slim waist and rounded derriere. Céleste’s long, slim arms, often noted as the most striking of her many physical features, were fully exposed. She undulated just short of a swivel to a table with her friend Frisette, herself eye-catching but a mere shadow in this moment. Céleste removed her bonnet and off-white shawl, then ceremoniously slid off her gloves to expose her slender fingers.

The young men were nervous about approaching her, even though they were among the wealthiest members of France’s aristocracy. Some were afraid because it took courage to accost her, despite the well-accepted fact that women entering the café were seeking paying paramours. Others knew her reputation for saying “Non, monsieur; merci”. They feared her rejection beyond a drink or a meal. Such was Céleste’s fame that this once low-level prostitute could pick and choose any man with whom she wished to take favours, no matter how wealthy or important – an unusual situation even for the well-known actresses of the era. But then she was more beautiful than Empress Eugenie, Napoleon III’s Spanish wife. Even Queen Victoria, who made a hobby of describing the appearance of notables she met, thought so. It was said that the real princesses of France were the courtesans, who ruled by conquest.

But you’ve got to go through it all, to show the abuse and all that.

Elizabeth: So when they first see each other …

Roland: So she’s actually having a slanging match with some of the men in the café, because that’s part of the game, but she’s giving as good as she got. It’s all in the story, but at one point one of the dandies – he’s upset because she gave as much as she’s been given – he goes:

“Who brought this whore to the party?”, one of the tormentors asked with a vicious glare of defeat. Frisette wanted to leave, but game Céleste refused. At this point, a dashing dark-haired man intervened, and demanded reparations from the main offender for his unpleasant remarks. Céleste had never seen the man before. There was something intriguing about him. He had none of the effete accoutrements of the dandies, nor their patronizing manner which exposed insecurities. He was chivalrous and clearly an aristocrat. In fact, he was the 25-year-old Count Lionel de Chabrillan, the only man who could possibly take Céleste away from her notorious past. Would he be her first true love, and at last help her forget her miserable childhood?

Elizabeth: Beautifully written. (Applause.)

Roland: Well, it’s a lovely story to write, and I did have a bit of help, from her…

Elizabeth: Perhaps she was looking over your shoulder, Roland.

Roland: Well, if you believe in all that, it’s definitely odd that I’ve been bullied and pushed by myself in this book. And that moment on the Paris Underground – I didn’t tell you – that rejection – at the Théâtre Mogador, that was in the Underground…

Elizabeth: That’s what I was referring to earlier, that sign.

Roland: …when the agent rejected that idea. And Mogador was her (Céleste’s) stage name.

Elizabeth: Well, if we look, if we have our eyes open, I believe there are signs. Do you have a blog where my listeners can go to find out more about you?

Roland: Yes, it is Roland-Perry-dot-com-dot-au – that’s the website.

Elizabeth: One last question, and this is a signature question I ask all my guests: What do you wish for for the world, and most importantly for yourself?

Roland: Well, I’ll start with me first because I’m more important than the world in my idea. I want another 30 years of healthy productivity in work, and I want to see most of the really good narratives into movies. For the rest of the world I have no hope whatsoever, so I have to have hope for myself.

Elizabeth: Well, I’m very pleased you have hope for yourself and I hope you get to benefit from the next 30 years too.

Roland: And I’m not asking for world peace – you’re not going to get it, honey, in your lifetime or your children’s.

Elizabeth: Professor Roland Perry, thank you so much for guesting on Writers’ Tête-à-tête with Elizabeth Harris. We look forward to more of your stunning work over the next 30 years.

Roland: Thank you very much.

Elizabeth: Thank you everyone, and may your wishes come true.

[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

No comments yet. Be the first to say something!